PORTLAND, Ore. – When politics got rough for Mark Hatfield, he headed to a Catholic church to pray.

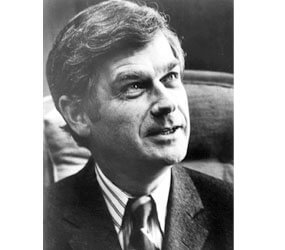

The former U.S. senator from Oregon, a prominent advocate of nonviolence, died Aug. 7 at 89. One of the nation’s most influential lawmakers for decades, Hatfield was a Baptist Republican with high regard for Catholic social teaching. He had a habit of walking to St. Joseph Church on Capitol Hill to clear his head.

“When you’re praising God, you’re taking your thoughts off yourself,” he once told the Catholic Sentinel, newspaper of the Portland Archdiocese.

Hatfield, who had been ill for several years, died at a care center in Portland.

He was Oregon’s governor for eight years before serving in the Senate from 1966 to 1996.

In a 1994 interview with the Catholic Sentinel, Hatfield said he saw himself as a statesman taking Jesus as the ultimate role model.

“It was totally revolutionary and is still revolutionary to think that a leader is a servant,” Hatfield said. “I try not to be the manipulative powerful leader on the white charger, but the servant leader.”

Among his heroes were spiritual writer Father Henri Nouwen and Blessed Teresa of Kolkata, whom he met. But he said he gained the most “spiritual power” from regular people who prayed for him.

Catholic friends kept him supplied with their literature, including the writings of Blessed John Paul II.

“So far it sounds like good Baptist doctrine to me,” he told the Catholic Sentinel, being impish but also showing that he thought the denominations had much in common.

In a 2002 address to an annual banquet for Catholic Charities of Portland, Hatfield got a laugh when he noted that he was a Baptist, which with 23 different denominations “multiplies by dividing.”

Over the years Hatfield received many honors, including an honorary law degree from The Catholic University of America School of Law in 1989, as his daughter received her law degree there, and the Poverello Medal from the Franciscan University of Steubenville, Ohio, in 1974, awarded annually “for Christ-like benefactions in imitation of St. Francis of Assisi.”

Hatfield was born in the Willamette Valley farm town of Dallas in 1922, son of a railroad blacksmith and a woman who would become a teacher. Both parents were Baptists.

As an Oregon lawmaker in the 1950s, Hatfield was an early supporter of civil rights. Elected governor in 1959, he emerged as a rising moderate Republican star. He gave a speech at the 1964 Republican convention and denounced far-right politics. In 1966, he was the only governor to vote against a resolution supporting the Vietnam War.

Later that year, he was elected to the Senate on an anti-war stance. Throughout his long career in the Senate, Hatfield sought to shrink defense spending and counter poverty, hunger and disease.

In 1991, he stood on the Senate floor and cast the only vote in opposition to President George H.W. Bush’s Operation Desert Storm. Saying war is futile, he attributed his abiding position to experiences as a naval officer during World War II, duty that brought him to Hiroshima a month after the atomic bomb had been dropped.

“The smells of decomposition were still there in the air with the sights of utter devastation in all directions,” he said. “It really impacted me.”

Some wags dubbed him “St. Mark.”

But along with taking the high road, he was a deft politician who brought an estimated $3 billion in federal money to Oregon, especially when he became chairman of the Senate Appropriations Committee in 1981. Enemies included environmentalists, who saw him as too cozy with the timber industry. Hatfield did, however, win praise for preserving beaches, the Columbia River Gorge and some forests.

He worked to chip away at government regulations, convinced federal authority had grown at the people’s expense. But he voted against a federal balanced budget amendment in 1995, infuriating neo-conservatives.

He survived two funding scandals and was once rebuked by the Senate Ethics Committee. Yet he was admired by many Catholics because he was pro-life, anti-war and anti-death penalty.

He told the Catholic Sentinel that he was proud of his consistent position in favor of life. He linked violent crime to tolerance of abortion, executions and warfare.

After he retired, Hatfield joined Catholic leaders in a failed attempt to abolish the death penalty in Oregon.

“Senator Hatfield took courageous positions of conscience in the face of substantial political opposition,” said U.S. Sen. Jeff Merkley, D-Ore. “He inspired many to public service, encouraging them to work to do what is right rather than what is convenient or popular.”

Gerry Frank, Hatfield’s longtime aide, said the senator’s faith was “helpful in hard times and key all the time.”

Hatfield spent some of his retirement at an assisted living community built on the convent grounds of the Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary near Portland.

He is survived by his wife and four children. Plans call for a private funeral and a public memorial service at a later date.