By Maria Wiering

Twitter: @ReviewWiering

OVERLEA – It was April 1945, 11 months after his B-24 Liberator was shot down near Berlin. Surviving on potatoes intended for swine, Walter Czawlytko and thousands of other prisoners of war marched west across Germany, away from approaching Russian forces.

They had already been walking – from winter into spring – for two months.

Men fell out of line, too weak to go on. German soldiers left them for dead, and Czawlytko took note. Truly weak, exhausted and ill, the 20-year-old airman left the road to lie in the ditch. After other prisoners and guards shuffled by, he sought cover in a forest and found others who had escaped the same way.

They were free, but still not safe.

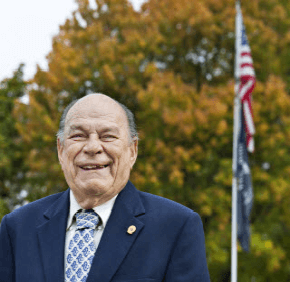

Now 87, Czawlytko tells his oft-recounted story in a straight-forward way, its events like verses of a familiar song. Marie, his wife of 65 years, reminds him to include details he inadvertently skips. He recalls his experience with dates and without hyperbole.

Now a parishioner of St. Michael, Overlea, Czawlytko, one of 10 siblings raised by Polish immigrants, grew up in Canton, two blocks from St. Casimir Parish and school. An altar server, he remembers his mother rousing him to ready the church’s bells for the 6 a.m. Angelus.

It was at St. Casimir that he developed a deep devotion to the Blessed Virgin Mary that would sustain him during and after the war.

Two months after turning 18, he was drafted into the U.S. Army and assigned to the Army Air Forces. He arrived in Great Britain June 6, 1944 – D-Day – four days before he turned 19.

Three weeks later, he flew his first combat mission over Germany as a left-wing waist gunner. The next day, while targeting an aircraft factory near Aschersleben on his second mission, his plane “Abel Mabel” was shot down.

He crossed himself and jumped, curled in the fetal position as instructed. His parachute deployed, he dropped 4,000 feet into a tree near a farmhouse. As he dangled, a woman came out with a butcher’s knife, stabbed his shoulder and cut along his arm. At first Czawlytko thought she might kill him, but he now suspects she was seeking money, maps or his chute’s silk; German soldiers arrived before he could find out.

He was interrogated for three days. “Name, rank and serial number, that was all you were supposed to give them,” he said. A German officer accused Czawlytko of being a Russian spy, and a soldier struck him in the face with his rifle butt, knocking out some of Czawltyko’s bottom teeth.

About 100 American flyers were stuffed into a train car for the four-day trip to the prison camp, or “stalag.” At the camp – Stalag Luft IV at Kiefheide, near Goss Tychow in present-day Poland – the men passed the days with walking, conversation and debate.

Twenty-four men lived in a 12-foot-by-12-foot barrack. Praying for liberation, they suffered with lice and dysentery and ate little, but they received some goods from Red Cross parcels, picked-over first by German soldiers.

At one point, a Polish priest visited the men, and Czawlytko was one of the few who understood the language. The priest heard his confession and gave him a brown-beaded rosary.

As the Russian Army advanced and allied forces gained ground, German soldiers forced 6,000 airmen to leave the camp on foot in early February 1944 on what would become known as a “death march” through deep snow, blizzards and below zero temperatures.

Told their march would last three days, men dragged on for weeks, then months.

Herded in groups on different routes, the men slept in barns, fields or forests. Food was scarce. Some, according to historians, ate rats raw. For those who endured, the march covered 600 miles over 86 days. An estimated 1,300 died before they were liberated by American and British forces.

“It is a tribute to man’s human spirit and his will to live that so many of us survived,” Czawlytko would later say in “We Regret to Inform You” by William Rutkowski, a compilation of POW stories first published in 2001.

Czawlytko told the Catholic Review he credits his devotion to Mary for his courage during captivity.

“I’m very fond of the Blessed Mother, and grew up that way,” he said.

The only time he truly remembers being afraid was while hiding in the forest after escaping the march.

Ground troops were fighting in the area, and mortars were falling around the escapees. They moved toward the British troops, and after a few days, British soldiers discovered them in the forest. They confirmed Czawlytko and the others were U.S. airmen and sent them to a hospital in Le Havre, France.

He had dropped from 180 to 98 pounds and developed digestive problems that would afflict him throughout his life. While Czawlytko was sailing home on a hospital ship in May 1945, victory was declared in Europe. His four enlisted brothers also eventually came home.

Czawlytko was discharged from the Army Air Forces, but was frequently ill. He spent much of his early 20s in and out of Fort Howard Veterans Hospital.

He married Marie Trczinski Oct. 25, 1947. The couple have five children, 15 grandchildren and 11 great-grandchildren.

Czawlytko worked for the Veterans Administration for 15 years, and then as a Baltimore police officer until he retired in 1987.

In written accounts, Czawlytko describes suffering from flashbacks and physical disabilities throughout his life. “C’est la guerre,” he told the Catholic Review – “such is war.” “What’s going to happen is going to happen,” he said.

Veterans Day, Nov. 11, continues to carry meaning, 67 years after his death march. More than 142,000 Americans have been held as prisoners of war since World War I, according to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Ninety percent of living ex-POWs are World War II veterans such as Czawlytko. About 740 World War II veterans die every day.

Czawlytko belongs to a litany of veterans organizations, including Maryland’s Catholic War Veterans chapter. A Purple Heart is among the service medals framed in his living room.

“I did my part of what I was asked to do at that time,” he said.

He still prays with the rosary he received in Stalag Luft IV.

“I talk to Mary,” he said, “and she talks to me.”

Czawlytko at war

June 10, 1925 – Born in Canton

Aug. 5, 1943 – Received draft notice, began training shortly thereafter

June 6, 1944 – D-Day; Czawlytko arrived in Great Britain

June 28, 1944 – First combat mission

June 29, 1944 – Second combat mission, taken POW

July 3, 1944 – Arrived at Stalag Luft IV

Feb. 3, 1945 – Began “death march”

April 8, 1945 – Escaped march (approximate date)