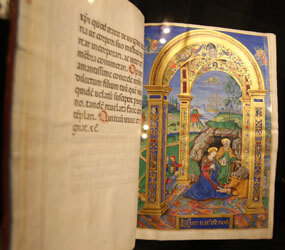

In many ways, it’s the quintessential image of Christ’s birth.

With her hands folded in prayer and a golden halo encircling her equally golden hair, the Blessed Virgin Mary kneels before her newborn son. A white-haired Joseph stands nearby, carrying a lantern. Animals recline near the serene babe, while a bearded shepherd gazes at winged angels overhead.

Yet other elements seem out of place. A highly ornate baldachino, a canopy-like structure found over church altars, towers above the holy family. A cave is seen in the background, and medieval spires poke out from the hills in the distance.

The brightly painted image, contained in an early 16th-century Catholic missal commissioned by Cardinal Patriarch Marco Cornaro, is the centerpiece of a special exhibition now on display at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore.

“The Christmas Story: Picturing the Birth of Christ in Medieval Manuscripts,” features depictions of events related to Christ’s Nativity as portrayed in a variety of liturgical prayer books. They include the Annunciation, Christ’s birth, the angel’s announcement of Christ’s arrival, Herod’s slaughter of the Holy Innocents, Christ’s first bath and his circumcision.

Ben Tilghman, a Walters’ curator, said the Cornaro Missal’s depiction of the nativity represents not merely a “pretty illustration,” but a means to convey symbolic theological ideas.

“What you see here is the most beautiful, most highly decorative page in the whole book,” Tilghman said. He gestured toward the famous missal, which is opened to the illumination of the Nativity and protected in a climate-controlled display case like the other featured books.

The major elements of the artwork, some of which seem anachronistic, have religious significance, Tilghman said. The cave comes from an apocryphal Eastern tradition that Christ was born in a cave. The baldachino and the marble flooring on which the Holy Family stand are eucharistic references to the altar. They look ahead to Christ’s sacrifice even at the moment of his birth, Tilghman said.

“That’s probably why the animals are so close to him,” Tilghman explained. “In some other pictures, Christ is in a manger with hay and the animals are leaning over him. It’s this idea of conflating him with the wheat – equating him with the bread and the body.”

A cloak worn by the Blessed Virgin Mary is painted in a deep, rich blue. Tilghman believes the striking color was made from lapis lazuli – a rare stone obtained in Afghanistan that was ground into powder and mixed with egg and water to make stunning azure paint.

“It was very valuable,” Tilghman said. “Sometimes, it was more expensive than gold, which is one of the reasons why the Virgin was always in blue. It makes it more precious.”

The Cornaro Missal, on loan to the Walters, was crafted by an unknown Italian Renaissance artist around 1503. The masterpiece was later acquired by the Austrian branch of the Rothschild family. It was stolen by the Nazis, and was returned to the Rothschilds after World War II. Sold at auction in 1999 for more than $4.4 million, the missal is now part of a private American collection.

Several illuminations from the Walters’ own collection are also on display in the Christmas exhibit. The oldest item is a 1262 Armenian illumination by Toros Roslin that shows the Nativity with the Adoration of the Shepherds. There is also a rare Ethiopian illumination.

Because the pigments used in the illuminations are vulnerable to damage, Tilghman noted that the images will not be shown again for five years.

“When we have one of these pages open, we only do it for three months,” Tilghman said. “This is your chance to see it.”

The free exhibition runs through Feb. 28. Hours are Wednesday-Sunday, 10 a.m.-5 p.m. The museum is closed on Mondays and Tuesdays. Visit www.thewalters.org for more information.