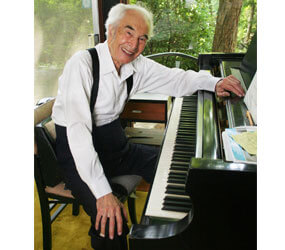

CINCINNATI – Music can be the language to help bring people together, crossing any nation’s boundary and driving freedom throughout the world, said jazz icon Dave Brubeck.

Fifty years after the taping of his signature tune “Take Five,” the musician will be honored Dec. 6 with a lifetime achievement award from the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington. In 2006 he was the recipient of the University of Notre Dame’s 2006 Laetare Medal.

Brubeck, 88, discussed faith, sacred music, jazz and the importance of cross-cultural and international exchange with St. Anthony Messenger magazine in an article in the October 2009 issue.

In 1958, Brubeck led his Dave Brubeck Quartet on a 14-country “goodwill” tour through Europe, the Middle East and Central Asia. The following year, the group recorded “Time Out,” the first jazz album to sell more than 1 million copies. The breakthrough album featured incorporated rhythms and beats from other cultures.

“Something I had wanted to do was to experiment in different time signatures,” Brubeck said, explaining that early jazz reflected “simple marching beats” and not the complicated African- and Asian-influenced rhythmic sounds of drum choruses.

Time, irregular meters and music drawing on other cultural idioms figure prominently in Brubeck’s music following “Time Out”: “Time Further Out” (1961); “Countdown: Time in Outer Space” (1962); “Time Changes” (1963); and “Time In” (1965).

“Jazz represents freedom, freedom musically and politically,” he said. He noted that his 1958 tour targeted countries such as Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq, Pakistan, Turkey and India and was meant to show “how important freedom is.”

“This kind of cross-cultural thing is something we should sponsor more because it is so important … to the world,” said Brubeck, who has performed for nine U.S. presidents and in 2008 received the U.S. State Department’s Benjamin Franklin Award for Public Diplomacy.

While known for jazz, his impact as a composer of orchestral pieces, a Catholic Mass and other sacred music has gone less noticed.

Brubeck acquired an interest in sacred music during World War II when he came up with the idea behind an oratorio based on the Ten Commandments. That musical fascination, especially with the prohibition “Thou Shall Not Kill,” took two decades before he finished his first major choral work, “The Light in the Wilderness.”

It was the composition of a Catholic Mass, “To Hope! A Celebration,” that had the most profound effect on Brubeck’s life, written at a time when he did not belong to a denomination or faith community.

When a priest asked him before its premiere in 1980 why there was no Our Father section of the Mass, Brubeck remembers first asking: “What’s the Our Father,” which he knew as the Lord’s Prayer.

He resolved not to make the addition that, in his mind, would have wreaked havoc with the composition. He said he told the priest he couldn’t think about it at the time because he was just about to go on vacation with his family.

But on the first night of the family trip he said he “dreamt the Our Father” and hopped out of bed to write down as much as he could remember.

“That’s when I decided they are trying to tell me something,” he said, deciding right then to add that piece to the Mass and to become Catholic.

He has adamantly stated for years that he is not a convert to Catholicism, saying to be a convert one needs to be something first. Instead, he has defined himself as being “nothing” before being welcomed into the church.

Brubeck’s Mass has been performed throughout the world, including in Russia in 1997 and before Pope John Paul II 10 years earlier in San Francisco during the pontiff’s pilgrimage to the United States. At that latter celebration, Brubeck was asked to write an additional processional piece for the pope’s entrance in Candlestick Park.

Once again, it was a dream that led him to complete a sacred music project that he initially refused as not workable.

“They needed nine minutes and they gave me a sentence, ‘Upon this rock I will build my church and the jaws of hell cannot prevail against it,’“ he said. Brubeck dreamt that Bach would have taken one sentence in a chorale and fugue, as he often did, and that was the answer, he said of the piece known as “Upon This Rock.”

With all of his awards and jazz-related achievements, the father of six children and husband of 67 years, describes “Upon This Rock” and “The Light in the Wilderness” as his greatest musical accomplishments.

Brubeck also does not make a distinction between his work as an orchestral and chorale composer and his performances as one of the world’s most foremost jazz bandleaders. Jazz and the sacred, he added, “have always been close.”

He said that throughout his career he has always been open to new ways of tackling a composition and pointed out that there has not been any duplication.

The musician likens his creativity to snowflakes that are never duplicated despite the billions that fall from the sky.

“If God can create like that,” Brubeck added, “we ought to be able to reflect a bit of that.”