TENOSIQUE, Mexico – The Franciscan-run migrant shelter La 72 has welcomed a steady stream of migrants since opening its doors in 2011 in this sweaty railway terminus near the Guatemalan border.

It has also endured a steady stream of harassment – from politicians and police officers, immigration officials and even organized crime – as it tended to people fleeing poverty and violence in Central America.

But the latest indignity inflicted on the shelter stunned the staff: insinuations of money laundering, an odd activity for the project of a religious order renowned for its vows of poverty.

“Effectively, our spirit as a Franciscan shelter is that: It’s austerity. It’s receiving few funds, and receiving many (migrants) with that money, and doing so with humility,” said Ramon Marquez, director of La 72 — so named to remember the victims of a 2010 massacre of 72 migrants in Mexico’s northern Tamaulipas state. “That’s why it makes no sense that they’re speaking about money laundering, of the misuse of money.”

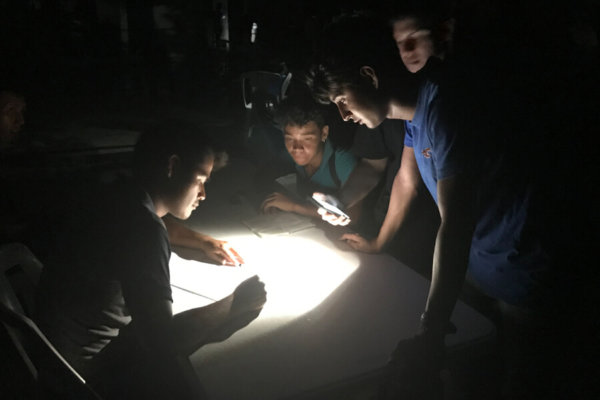

Migrant shelters in Mexico – including many affiliated with the Catholic Church – have long provided a safe place for guests to rest, refresh and reflect on rough journeys through areas rife with risks such as kidnap, extortion and rape.

The shelters also sometimes provide spiritual and psychological support for the thousands of migrants traveling through Mexico – a population often preyed upon by crooked public officials, unscrupulous smugglers and organized crime. And some shelters such as La 72 have histories of advocacy, promoting human rights and decrying corruption, which have caused conflicts with local authorities.

But with the Mexican government stepping up efforts to stem the flow of migrants through the country, shelters have come under scrutiny not seen since the laws prohibiting the provision of humanitarian assistance to migrants were removed in 2011. Three Catholic-run shelters have reported a series of incidents against them, including attempts at intimidation, incursions into their properties and to attempts by public officials to revise the papers of the migrants they’re hosting.

“We’re in very difficult times due to everything implied by this unprecedented flow of migrants that we’ve seen this year,” Marquez said.

“The radical turn in Mexican migration policy, the pursuit, detention and deportation (of migrants) and the closing of borders, this always comes accompanied by actions,” he added. “It’s always gone hand in hand with the criminalization and persecution of (migrant) defenders.”

Mexican President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador took office in late 2018, having promised to “not do the dirty work” of other countries on the migration issue. His administration started issuing humanitarian visas to migrants, allowing them to work and access social benefits in Mexico, but the program was halted due to crushing demand and perceptions migrants were simply using the documents to quickly reach the U.S. border.

U.S. President Donald Trump also tweeted his displeasure with migrants arriving at the U.S. border in numbers not seen in more than a decade. He threatened to slap escalating tariffs on Mexican imports until migration stopped. As part of a deal struck with the U.S. to avoid tariffs, Mexico deployed 6,000 members of its newly formed national guard to southern Mexico to stop migrants.

Lopez Obrador proposed creating the national guard to calm the country, but the national guard’s first deployment has been to the northern and southern borders to stop migrants.

Guard members knocked on the door of the Attention Center for the Migrant Exodus –a parish shelter in Agua Prieta, opposite Douglas, Arizona – June 23. They asked to check the migratory status of the shelter guests, shelter volunteer Perla del Angel told Catholic News Service.

“They argued with us that it was part of their powers as the National Guard,” del Angel said, adding the guardsmen spoke of “rescuing” migrants, a euphemism for detentions used by Mexican immigration officials.

In Chiapas state, staff at the Casa Betania Santa Martha shelter in the municipality of Salto de Agua found two municipal police officers sitting inside the premises, speaking with the migrants.

Divine Word Father Jeffrey Yague Udasco, the parish priest responsible for the shelter, said the police entered while staff were attending to migrants. When confronted, the police said they were collecting information for the local police chief, then changed their story say they were “taking a break.”

Father Yague told Catholic News Service information from the shelter would be useful for local police, who often work with human smugglers. Municipal officials would likely try to extract funding from the state government with the pretext of assisting migrants.

“Somehow, I think, it’s an attempt at intimidation, said Sister Diana Munoz Alba, one of the four Franciscan Missionaries of Mary who operate the shelter.

Compounding the shelters’ difficulties, Lopez Obrador alleged shelters had been mismanaging government money – something shelter operators found baffling because they depended exclusively on donations.

“We are attending to a reality the (government) historically doesn’t want to address,” Marquez said.

The most recent troubles for La 72 started when the Tabasco Economic and Property Intelligence Unit issued a statement June 18, saying it would “help in the detection of money laundering operations in migrant shelters in Tabasco’s territory.”

Alejandro Encinas, secretary of human rights, population and migration secretary, immediately denied ever signaling migrant shelters for scrutiny.

For Marquez, the damage was done. The statement’s target was easily identifiable, as La 72 is the only significant migrant shelter in Tabasco.

“We feel defamed,” he said. “We’ve spent eight years, working with more than 100,000 people and I believe our reputation has spoken loudly during this time.”