By Maria Wiering

mwiering@CatholicReview.org

Twitter: @ReviewWiering

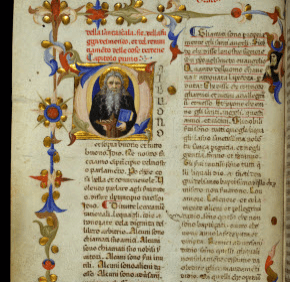

The Walters Art Museum is spotlighting the meticulous craftsmanship of medieval monks and nuns in an exhibition of illuminated manuscripts.

It displays the works “not as stagnant, dusty tomes, but living objects with remarkable stories to tell about a monastic culture that flourishes to this day,” according to the introductory plaque.

The Baltimore exhibition, “Living by the Book: Monks, Nuns and Their Manuscripts,” runs through Sept. 29 in the museum’s manuscript room. The books are presented both as artworks and everyday objects in medieval European monastic life.

The 19 manuscripts on display demonstrate the careful artistry that went into inscribing and illustrating – or “illuminating” – books for public worship, private devotion and education. They also provide a peek into the lives of the men and women who created them.

“I tried to look at different aspects – them (monks and nuns) as people, their books as guides to their lives, their books as a creative process,” said Lynley Herbert, exhibition curator and the museum’s assistant curator in the department of rare books and manuscripts. “They were creators and artists and thinkers, scholars and teachers.”

Many of the illuminations are tiny, brightly hued scenes. They’re tucked, in some cases, inside an inch-tall center of an initial letter – what Microsoft Word would call a “drop cap” – of the first phrase of a prayer. Others frame printed words or fill entire pages, such as an image of St. George slaying a dragon in a psalter. Most shine with gold leafing.

Several of the featured illuminations include images of monks and nuns present in common biblical scenes, such as the crucifixion, or kneeling in reverence before saints.

Other depictions are less pious. One page of a 14th-century French book of hours includes two nuns with wings and talons, a possible allusion to the thieving harpies of Greek mythology. Another French manuscript, dating to the 15th-century, shows monks grimacing at their monastic brothers’ poor singing.

The exhibition includes a few manuscripts that highlight the role of medieval monasteries in education and show that not all manuscripts were religious texts. One, a “friendship book,” was created by 17th-century students attending the Fulda Seminary in Hesse, Germany, and includes a full-page illustration of them playing tennis with their Jesuit instructors nearby. Other books are clearly academic, including the writings of Virgil and Aristotle – a Roman poet and Greek philosopher whose works have influenced Christian thought.

The exhibit’s gem – because of its importance, not necessarily its artistry – is the Walters’ prized St. Francis Missal, a 12th-century missal the Italian saint supposedly leafed through at the Church of San Nicolo in Assisi. According to legend, St. Francis opened the book to three random verses, all of which directed him to renounce earthly goods and embrace poverty. Because the manuscript was touched by the saint, it’s considered a second-class relic and is an object of pilgrimage from around the world.

Most of the works in the exhibition are from the Walters’ permanent collection, which exceeds 900 illuminated manuscripts.

“As much as people use digital technology, I think there’s still a love affair with the book for a lot of people,” Herbert said. “It’s certainly something that has a sort of romantic view in our minds, especially an 1,000-year-old book that has gold and is painted. There’s something almost magical that transports you back.”

Meanwhile, the Walters is digitizing its manuscript collection so that the books can be viewed online.

Response to the exhibition has been “overwhelmingly really positive,” Herbert said, adding that she has received affirming feedback from monks and nuns from around the world.

“What an extraordinary privilege to spend an afternoon traveling back in time to an era when faith was so central to existence and bred beauty of word and form not seen since,” one visitor commented.

The exhibition has attracted non-religious people, too, who have reported a better understanding of the role monks and nuns played in medieval culture and an appreciation of their contribution to western education, Herbert said.

The exhibit’s adjoining room reveals the laborious nature of manuscript-making through examples of parchment, tools and pigments essential to the writing and illuminating processes, as well as a video of a modern-day illuminator working at her craft.

Calligraphy and illumination are niche endeavors, but not dying arts, Herbert said.

“There definitely is a revival going on,” she said. “There seems to be a lot more people interested than there was even 10 years ago. … There’s almost a push-back against the lack of use of books these days. It seems like people are almost going backwards, and trying to cling back to this kind of very tactile creation of books.”

DID YOU KNOW?

– Monks and nuns were among the best educated people in medieval society.

– Monks and nuns’ efforts to copy ancient texts preserved works from ancient Greece and Rome that may otherwise have been lost.

– Pigments for medieval manuscripts were created, in part, by grinding minerals, plants, or animal parts, such as seashells. Oak galls, an oak tree deformity, were used to make ink. Mussel shells were commonly used to hold each pigment.

– Paper was invented in China in 105 A.D., but many medieval manuscripts were created with parchment or vellum, treated animal skins.

– Books replaced the scroll in 400 A.D.

Also see: