WASHINGTON — At the start of a mid-March gathering at Georgetown University, organizers asked church leaders, activists and members of indigenous communities to think of a person they knew who had worked in defense of the environment and to call out his or her name.

One called out “Berta Caceres,” a well-known Honduran environmental activist killed in March 2016. The soft-spoken Bishop Guy Charbonneau of Choluteca, Honduras, called out “Juan Lopez,” the name of a parishioner from the Church of San Isidro de Tocoa, a “delegate of the Word,” a Catholic Honduran jailed and, and like Caceres, threatened for speaking out against mining industries.

The Catholic Church in Honduras, as well as in the Amazon and elsewhere, supports those like Lopez because of the situations and consequences caused by the exploitation of natural resources and destruction of the environment. These situations include poverty, unemployment and insecurity, Bishop Charbonneau told Catholic News Service March 19.

Bishop Charbonneau was one of some 200 church leaders, activists and members of indigenous communities present for a historic three-day international gathering March 19-21 at the Jesuit university in Washington. Some of those who gathered there also will attend the Synod of Bishops on the Amazon in October, a gathering that Pope Francis has called for at the Vatican to discuss environmental issues, how they affect the region’s indigenous communities and what its environmental degradation means for humanity.

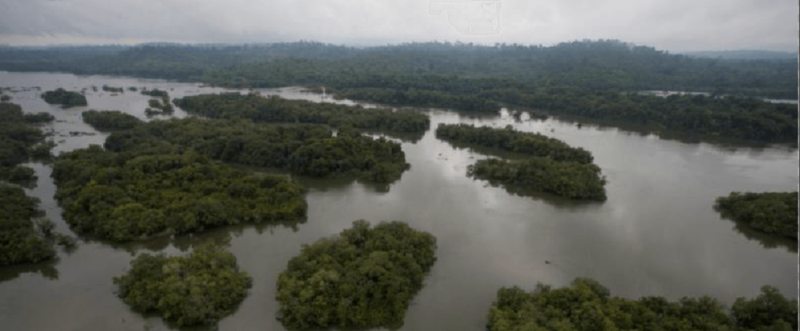

“Without the Amazon, Latin American goes under and, without (the benefits of) the Amazon for the planet, we all go under,” Jesuit Father Roberto Jaramillo Bernal, president of the Latin American Jesuit Conference, told CNS March 20 about the importance of finding a path forward on issues affecting the resource-rich South American region, home to a rainforest that, with its greenery, absorbs global emissions of carbon dioxide.

Fighting for the Amazon is an ethical matter, not just of defending God’s creation, as well as of defending “the least of these,” but what’s happening in the Amazon affects immigration patterns, hunger, poverty, medicine, political systems, not to mention the irreversible damage to a planet that humanity calls home and one that can’t be replaced, said Father Jaramillo.

“Sooner or later, this won’t just affect the indigenous people (of the Amazon), because natural resources are not infinite,” said Father Jaramillo. “This will affect the rich countries obsessed with consuming. They, too, will suffer the same consequences.”

The model of endless resources some countries tout is built on a lie, said Father Jaramillo, and it’s best to look at the finality of those resources to figure out how to act going forward. One way to do that is to change the mindset of people, he believes.

“Look at Romans 12:2,” Father Jaramillo implored. “St. Paul says renewal begins with the mind.”

For Father Jaramillo, changing that mindset, particularly about the limits of natural resources, is imperative in changing behavior that will mitigate any damage already done to the planet. In South America, the Catholic Church, through the Pan-Amazonian Church Network (known as REPAM for its acronym in Spanish) has done great work toward that goal, producing gatherings such as the one in Georgetown to figure out what the church must do, Father Jaramillo said.

“But it’s still a baby,” he said of the network, which will play a prominent role at the Vatican gathering. However, the work of the REPAM network is a ray of hope in the business of changing minds, he said.

The importance of the environmental mission in the eyes of the church was apparent by the prominent names of those present at the small Georgetown meeting: Cardinals Luis Antonio Tagle of Philippines, Claudio Hummes of Brazil, Charles Bo of Myanmar, Pedro Barreto of Peru and John Ribat of Papua New Guinea. At least two Vatican officials attended: Cardinal Peter Turkson, head of the Dicastery for Promoting Integral Human Development, and Lorenzo Baldiserri, general secretary of the Synod of Bishops. Archbishop Bernardito Auza, permanent observer of the Holy See to the United Nations, attended.

Bishops, activists, and members of indigenous communities from all continents discussed the science of environmental destruction; its socio-economic effects; the spiritual, economic and social connections made by indigenous communities and nature and what others can learn from it; the role of women in the fight of the environment; and possible ways the church and its members can help.

The higher rungs of the church also have some changing to do. Luxembourg Archbishop Jean-Claude Hollerich said during the gathering that Catholic institutions can look deeper into the environmental effects and practices of companies in which they might have a corporate stake.

“I urge Catholic institutions to continue divesting from companies that focus on fossil fuels,” he said. After all, customs and practices must be modeled from the top, and the church can show leadership in the way it, too, behaves in the marketplace, said Archbishop Hollerich, president of the Commission of the Bishops’ Conferences of the European Union.

Some participants mentioned some of the environmental successes that have come about with help from the Catholic Church. One of them includes El Salvador, where Catholic leaders were instrumental in passing a law banning metal mining in 2017, making the small Central American country the first in the world to outlaw the industry. The local church opposed metal mining because of the potential to harm El Salvador’s dwindling supply of clean water, and the Archdiocese of San Salvador is now fighting against the privatization of water, saying it will only harm the poor.

Those like Father Jaramillo also see part of the solution in learning from the indigenous communities and their relationship to the environment, “finding a more contemplative, more open way, more careful manner in caring for creation,” he said, before it’s too late.

“We need to change the parameters,” he said. “We’re not here to dominate creation, but to live with it.”

Copyright ©2019 Catholic News Service/U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops.