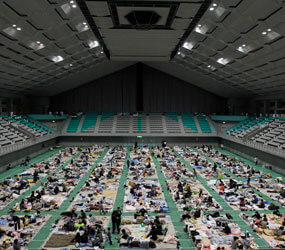

YAMAGATA, Japan – Kazuhiro Kikuchi, his wife, Kazuki, and two of their three children were staying at a large sports center-turned-evacuation center about 40 miles north of the Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant, where officials were struggling to contain a potential nuclear disaster.

Until March 16, the couple had remained in their home, about 30 miles away from the plant.

“We kept saying to each other, ‘It’ll be all right; it’ll be all right,’“ Kazuki Kikuchi told the National Catholic Register, a U.S. weekly.

“We even went outdoors,” added Kazuhiro Kikuchi, “to search for missing people.”

The couple said no one told them to leave their home – they were outside the evacuation perimeter originally set by the Japanese government.

“We finally realized that we had to flee,” said Kazuki Kikuchi. “We absolutely do not want our children to run the danger of exposure to radiation.”

Kazuhiro Kikuchi is a private contractor who has worked with the plant and was there March 11 when the earthquake and ensuing tsunamis knocked out the cooling systems for the plant’s reactors.

He told the Register that the way the government has handled the situation “makes me furious.”

“I do not want them to create an additional disaster,” he said.

He was working near the boilers on the 10th floor of the nuclear plant when the earthquake struck.

“All the steam pipes around me broke loose, and the conditions were incredible,” he said. “I could barely stand.”

Soon after that, he saw the tsunami racing toward him.

“That was beyond belief,” he said.

“When it got here, a huge overhang crashed into the building, some 10 to 15 yards high. Some 200 cars in the parking lot were all swept together,” he said.

Kazuhiro Kikuchi said the plant’s employees “knew the emergency manual, and we were able to evacuate quickly. There was no panic. But people were, of course, scared and surprised.”

That has been typical of residents affected by the disaster.

“Today the dominant feeling is fear,” Father Daisuke Narui, executive director of Caritas Japan, said March 15. “The biggest concern is that of the nuclear power plant in Fukushima. It is a ghost from Japanese history coming back to haunt us. But it must be said that the people are not indulging in panic; instead, they are reacting with poise and dignity.”

Kazuhiro Kikuchi could not leave the plant until March 12, and it took even longer before he knew his children were still alive. Now his former source of income has become a source fear.

“I expect the worst,” he said.

On March 19, Japan increased its rating of the crisis at Fukushima Dai-ichi, increasing it to a level five on a scale of seven. This makes it the equivalent of the impact of the 1979 Three Mile Island crisis in the United States. But no one was sure how the crisis would end.

The Kikuchis are worried about the people they left behind. One family member is in the hospital, too weak and ill to travel. His wife stayed with him. One of their sons, who works with their city’s Chamber of Commerce, has also stayed behind.

“He is helping with preparing the area against radioactive fallout,” said his mother. “He is working so hard.”

The couple were furious about the lack of information.

“We are told nothing,” Kazuki Kikuchi said.

“And they also say nothing on television, right?” her husband added, referring to the complaint by Japanese media that there are many press conferences that clarify very little, if anything. “They show nothing but images of the explosion, but we don’t know whether radiation was released or not. There is a lack of truly clear information.”

“Because of that, there are lots of people who do not understand the situation,” Kazuki Kikuchi told the Register.

“They don’t realize the terror that Fukushima represents,” her husband added. “They don’t know the problems that radiation can cause them.

“This is not just some obscure accident,” he said. “The electricity company and the government have the obligation to carefully publicize the information they have. Their negligence to do this and the time they are wasting this way could cause far more serious and troubling conditions.”