VATICAN CITY – Intellectual curiosity about a very particular aspect of Christian pilgrimages to Jerusalem has gotten under the skin of Israel’s ambassador to the Holy See.

Mordechay Lewy, the ambassador who has an academic preparation in medieval history, is a student of Jerusalem pilgrim tattoos.

Members of the Vatican diplomatic corps have a variety of interests and specializations – there are several theologians and physicians among them, as well as career diplomats – but Lewy said, “it’s true, I don’t have many colleagues to talk with” about tattoos.

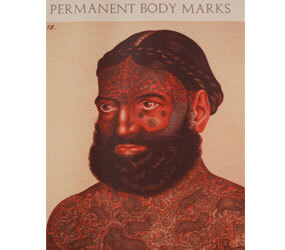

The ambassador is very serious about the subject, which involves questions about identity, art and local cultures, so he organized an international conference Dec. 5-6 called, “Into the Skin: Identity, Symbols and History of Permanent Body Marks.”

The conference brought together scholars from Israel, Europe, North America and New Zealand to explore the history of tattoos, the use of permanent body markings in a variety of cultures, tattooing techniques, social and religious attitudes toward tattooing and the tradition of pilgrim tattoos both in Jerusalem and in Loreto, Italy, site of what many believe is the house of Mary.

Ambassador Lewy said he basically stumbled upon descriptions of the Jerusalem pilgrim tattoos when, in the mid-1980s, he was posted to Sweden and was reading Swedish pilgrim diaries from the Middle Ages.

At that time, the ambassador said, he was “a lone detective looking for sources” that would explain the “body painting” reported to have marked many of the returning pilgrims. His first published article on the tattoos appeared in 1992.

The December conference at the Pontifical Urbanian University was a sign of how many connections he has made with other scholars over the past nine years; he said he hoped the connections would expand with the development of a website that would include an image bank of drawings and photos the scholars have collected.

In many Western cultures, there has been a strong aversion to tattoos and permanent body markings or scarring, which may be traced to a Judeo-Christian idea that one should not intentionally alter the human body because it is a divine creation, speakers said.

Throughout history, the ambassador said, people have been tattooed both voluntarily and involuntarily. The obvious recent example of the latter was the Nazi practice of tattooing identification numbers onto the arms of prisoners at the Auschwitz concentration camp.

“Personally, I would never tattoo myself,” Lewy said. “The idea for me is a challenge,” but one he is dealing with as a historical phenomenon.

Still, he said, “I understand my compatriots who feel a deep aversion even to dealing with it as a historical subject.”

But participants at the conference said Christians, particularly in the Middle Ages, were not wholeheartedly opposed to tattooing.

A Christian pilgrimage tattoo was “a small martyrdom – a public shedding of blood” for one’s faith, said Guido Guerzoni, a professor at Milan’s Bocconi University.

“A devotional tattoo was a sign of unshakable, immovable faith,” he said.

Ambassador Lewy said the earliest mention of permanent pilgrim markings he’s found is a 1484 reference to “branding marks” for pilgrims, but Eastern Christians in the Holy Land – particularly the Copts, Ethiopians and Armenians – seem always to have marked themselves permanently with the cross, either on their wrist or their forehead.

“It is a typical practice in the Orient, one that never died out and was adapted by the pilgrims. They didn’t have to invent it,” he said.

The ambassador said it was a myth that European Christians setting off for the Crusades in the 11th-13th centuries, tattooed themselves prior to battle so that if they were killed, they could be identified and given a Christian burial.

But William Purkis, a lecturer in medieval history at the University of Birmingham, England, said there is written evidence that some Crusaders, in taking up the cross, went a step further than most, who sewed a cross onto their clothes: some branded, scarred or tattooed a cross into their flesh. Some even claimed to have received the cross in their flesh – like a stigmata – in a miraculous way.

“The meaning of these markings, be they self-imposed or divinely bestowed, appears to have derived from the fact that from the outset, the Crusade was presented to the faithful” as a way of imitating Christ, following his example by “taking up the cross, by walking in his footsteps, and by suffering in the holy places where he had suffered for mankind,” Purkis said.

Sister Luigia Busani, a member of the Franciscan Fraternity of Bethany and the archivist of the Holy House of Loreto, said historical records show a practice of pilgrims to Loreto getting tattoos attesting to their pilgrimage from the late 16th century up until the 1960s.

At the beginning, she said, “the church tolerated tattooing as long as it involved religious symbols.”

Officially, Italy outlawed tattooing – citing health concerns – in the late 1800s and the practice in Loreto went underground. Sister Busani said that until the 1960s, pilgrims, and residents of Loreto, would still get tattoos by going to local shoemakers, who had needles, ink and the wooden blocks on which the traditional pilgrim tattoo patterns were carved.

Lewy brought a collection of wooden blocks from the Holy Land to the conference. Most include scenes of the Resurrection. The Jerusalem cross – a large cross with four small crosses in each corner – is a common symbol, but only after the 1500s, he said.

The wooden blocks were used like rubber stamps are today: a means of quickly making multiple copies of the same image. The pilgrim’s arm would be stamped, and the tattoo artist would use a needle to prick the image into the skin. An inked cloth would be wrapped around the bleeding arm so that the ink would sink into the wound, leaving a permanent image, he said.

Bearing on one’s skin an indelible reminder of a strong religious experience may be a thing of the past, the ambassador said. It’s not because people with that kind of faith are disappearing, but because “with laser technology, permanent body marks probably soon will be a matter of the past.”