By George P. Matysek Jr.

gmatysek@CatholicReview.org

Huddled in a wet corner of a cramped North Vietnamese concentration camp, Luke Le Sinh whispered prayers as his emaciated cellmates slept beside him. Careful not to let the guards see that he was praying, the former South Vietnamese army major had no choice but to count the Hail Marys and Our Fathers of the rosary on his fingers since the Communists had long ago confiscated his beads when they captured him in 1975.

For Le Sinh, the secret nightly ritual was his only source of encouragement during a 10-year imprisonment that broke the minds, bodies and spirits of many of his countrymen.

“Every day, I offered my sufferings to the Lord and to the Blessed Virgin Mary,” said Le Sinh, whose wife and 10 children were forced to harvest rice fields during his long political imprisonment. “It was very horrible,” he said. “It is a miracle that I survived. God protected me.”

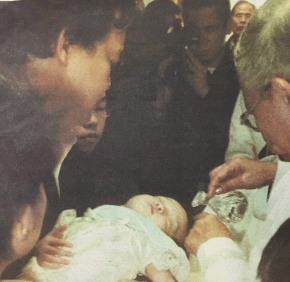

Daily dedication to prayer and the rosary has become a way of life for Luke Le Sinh since his imprisonment. (Amy Buck/CR Staff)

Having subsisted on little more than two bowls of rice and a cup of coffee a day, when Le Sinh was finally released in 1985, his body weight was half what it was when he was captured. But spiritually, the painful experience nourished his soul in ways he never anticipated.

“I became closer to God,” said Le Sinh, now a 70-year-old parishioner of the Vietnamese Catholic Community of Baltimore. “I didn’t have any anger. The church says I must forgive. I have forgiven.”

Le Sinh’s story of a long-suffering faith is not unfamiliar among the 300 parishioners who make up Baltimore’s tiny Catholic Vietnamese community. Like Le Sinh, many parishioners are former prisoners of the Communist government in Vietnam who had once worked for the American-supported South Vietnamese regime that was overrun by Ho Chi Minh in 1975.

Others are former boat people who fled their homeland to live a life free from the persecution that so often confronted Catholics in that war-torn part of Southeast Asia.

Still others are students who have come to this country in search of an education or jobs.

“Our people have known a lot of hardship,” said Khoa Nguyen, a 35-year-old parishioner who escaped from Hue in central Vietnam by spending 24 days on a boat headed for Hong Kong. “Their faith becomes stronger by their experiences. When they come to this country, it looks like the Promised Land to them. “We feel very fortunate to be here.”

Since most members of the Vietnamese community do not speak English, they look to their church as a special place where they can worship God in their own language and pass on their cultural traditions.

Worshipping in the small Vietnamese Cultural Center in Rosedale, parishioners come from all over the Baltimore metropolitan region and from as far away as Columbia, Bel Air and Glen Burnie.

“They are very committed to the church,” said Christian Brother John Chung Nguyen, temporary pastoral administrator of the community.

Because the parish has been without a pastor since June 1998, parishioners take turns driving to Gettysburg to bring a retired Vietnamese priest, Father Hy Hilarius Tran, to celebrate their community’s two Vietnamese-language Masses at 9 and 11 a.m. every Sunday.

They are now praying that a Vietnamese-speaking priest can soon be found to lead them and help them realize their dream of someday building their own church. At the community’s current facility, Masses are so cramped that worshippers often crowd the stairs. For bigger celebrations such as weddings and Easter Masses, parishioners use the Shrine of the Little Flower in East Baltimore.

“We are looking all over the country to find someone who can help us as pastor,” said Brother John, a Calvert Hall College High School computer teacher. “The people really want their own pastor.”

It has been the church that has been most supportive in helping parishioners adjust to a culture that’s very different from the one in which they grew up, Le Sinh said.

“They found jobs for my children,” the church lector noted. “When we first came, they gave us food and clothes for two months.”

Hong Van Nguyen, who arrived in America from Hue early this year after marrying Khoa Nguyen, said the Vietnamese Catholic Community immediately made her feel at home. Members taught her how to shop in the market, how to use the telephone and how to cook in an American kitchen.

“In Vietnam, I studied about American life at the university,” said the 27-year-old housewife. “but it is very different here. It is very difficult to understand the language and the culture. The Vietnamese Catholic Community helped me.”

The commitment to the church and an intense desire to see their Vietnamese Catholic culture passed on to their children is what motivates parishioners, said Khoa Nguyen, an Abingdon resident.

“I can go to American churches,” he acknowledged. “But I feel that I need to stick with the Vietnamese community. I can participate more and share the same culture.”

As they adapt to their new home, Le Sinh said it will be their common Catholic faith and culture that will hold his community together.

“I want my children to understand what we went through in Vietnam,” he said. “We need the church to help us to teach the culture of our country. We can’t forget.”