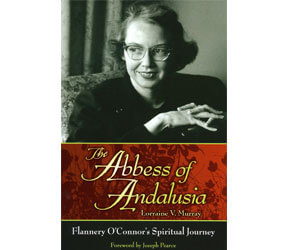

In her new book, “The Abbess of Andalusia,” Lorraine Murray aims to “uncover the self-portrait Flannery (O’Connor) created in the daily stream of letters that poured out of Andalusia,” the Georgia farm where the writer lived for 13 years until her death in 1964, when she was only 39.

That this Southern Catholic novelist – perhaps remembered even better for her short stories – was a prolific letter writer is well known. Nonetheless, the self-portrait that emerges here is refreshing. In it O’Connor is viewed as a woman of robust humor, a dedicated friend to many, a hardworking, disciplined composer of fiction and someone who experienced suffering firsthand, diagnosed with lupus when she was 25.

“I have never been anywhere but sick,” O’Connor said. Apparently, though, if poor health found ways to consume her physically, it never consumed her spiritually.

For Murray, the spirituality plainly manifested in O’Connor’s self-portrait is paramount. O’Connor’s letters reveal “an extraordinary spiritual life beneath the deceptively ordinary surface,” Murray writes. It has been said, she notes, that O’Connor “recognized the sacramental element in all of life.”

Along with O’Connor’s spirituality, Murray wants to bring to the fore the Catholic dimension of O’Connor’s life not only as a writer, but as a person for whom the Eucharist was “the center of existence.” This book asks what kind of Catholic O’Connor was.

Is this a question people still ask? It is, I have found. Many take pride in O’Connor as a leading 20th-century American Catholic writer. However, participants in a discussion group I was part of a few years back found her Catholicism difficult to comprehend. Was she liberal? Conservative? Progressive? Reactionary?

To comprehend what kind of Catholic O’Connor was, I expressed my view to the group that she needs to be anchored firmly in the Catholicism of the 1950s, for example, but not of the 1980s or a later period; the temptation to fit O’Connor into the familiar molds and movements of our own times is a temptation to resist. I felt that Murray was struggling with this very temptation at several points in her book.

So, will readers discover in the book what kind of Catholic O’Connor was? Yes, I think that for the most part they will. Murray did her homework and allows readers to view O’Connor’s somewhat complex self-portrait for themselves.

Thus, O’Connor comes forward as profoundly Catholic, yet not reluctant to take to task what she considered superficiality or to criticize what she termed “pious pap.”

O’Connor criticized priests who offered “oversimple solutions to complex problems,” Murray notes. Yet, other times O’Connor was “quick to defend the clergy against … unfair attacks,” expressing an understanding of the burdens placed on priests’ shoulders.

Murray says that “overly emotional prayers annoyed” O’Connor, but the prayers in a short breviary for religious and laity “suited her just fine.”

O’Connor “abhorred stories about saints that made them seem sickeningly sweet,” Murray writes. She also describes O’Connor as “fiercely Catholic,” a woman convinced that “all human life is precious” and that “love always triumphs over suffering.”

Chapter 6 in Murray’s book examines O’Connor the writer. I recommend this chapter to all aspiring writers, particularly writers of fiction, who may find the way she crafted stories astonishing.

Not surprisingly, writing “was indeed difficult” for O’Connor, Murray says. But O’Connor took her vocation “very seriously”; even when very ill “her chief concern was completing her stories.”

Of course, how O’Connor’s Catholicism factored into her writing continues as a topic of interest for many. Murray recalls O’Connor writing of her sense “that being a Catholic has saved me a couple thousand years in learning to write.”

I welcomed Murray’s inclusion of a comment made just days after O’Connor’s death in August 1964 by Atlanta’s Archbishop Paul Hallinan, who praised her in an archdiocesan newspaper column.

Archbishop Hallinan described O’Connor as a writer who served “the cause of the supernatural by a working knowledge of the secular.” He said, “Our South and our church are poorer because of the death of this fine young writer.”

Gibson was the founding editor of Origins, Catholic News Service’s documentary service. He retired in 2007 after holding that post for 36 years.