JERUSALEM – A new exhibit of never-displayed manuscripts written by Isaac Newton reveals the scientist’s fascination with theology and apocalyptic and biblical writings.

Best known as the rational 17th-century mathematician and physicist who discovered the notion of gravity, Newton is considered one of the foremost scientific intellects of all time.

“During that period religion and science were often connected with each other,” said Yemima Ben Menachem, curator of the exhibit and philosophy professor at Hebrew University in Jerusalem, where the papers are on display. “Most of the great scientists of the 17th century were religious in different ways. Newton was also a very religious man.”

In addition, she said, his writings reveal Newton as a very secretive man who believed in a personal, father-like God who sometimes intervenes in the world.

“His religious beliefs didn’t change his science, and he still remains as one of the great examples of great science,” said Mr. Ben Menachem.

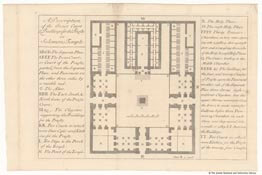

Mr. Ben Menachem said Newton viewed both nature and Scriptures as holding hidden messages that could be unraveled. She said he believed the secrets of the holy writings could be decoded by studying not only the written word but also things like the dimensions of the ancient Jewish Temple and tabernacle as described in the Bible and Talmud, a Jewish holy book.

Other documents contain sketches of the Temple, a verse from a Jewish prayer written painstakingly in Hebrew letters and references to Newton’s rejection of the Trinity. Newton felt there was only one God and although Jesus was the Son of God, he was not God himself, said Mr. Ben Menachem.

Newton did not make his views public for fear sanctions, including dismissal from his work, would be imposed against him, said Mr. Ben Menachem.

She said he approached his writings on Judeo-Christian prophecy with a religious fervor that showed he thought of himself and other scientists as prophets of sorts meant to unravel the secrets of nature.

“He thought the prophecies and biblical Scriptures were one way to know God, but there was … a direct way to know him also, through nature,” she said.

In one 1704 document Newton calculated the end of the world to be not earlier than 2060, based on a phrase from the Book of Daniel, Chapter 12, Verse 7, which reads: “and I heard him swear by him who lives forever that it should be for a year, two years, a half-year; and that, when the power of the destroyer of the holy people was brought to an end, all these things should end.”

According to the exhibit Newton interpreted this phrase as meaning that 1,260 years would pass from the establishment of the Holy Roman Empire under Charlemagne in 800 to the end of time.

“It may end later, but I see no reason for its ending sooner,” Newton wrote in his precise cramped script. “This I mention not to assert when the time of the end shall be, but to put a stop to the rash conjectures of fanciful men who are frequently predicting the time of the end, and by doing so bring the sacred prophecies into discredit as often as their predictions fail.”

Mr. Ben Menachem said Newton’s preoccupation with apocalyptic prophecies grew from the great interest in the topic in his time.

“On one hand he thought the end of days would come according to God’s plan and there was nothing humans could do about it, and they should not prophesy about it, but because there were people of the time saying the apocalypse was soon going to be upon them” he felt he had to speak out, she said.

In another document Newton interpreted biblical passages as indicating the Jews would return to the Holy Land before the end of time.

“The ends of days will see the ruin of the wicked nations, the end of weeping and of all troubles, the return of the Jews’ captivity and their setting up a flourishing and everlasting kingdom,” he wrote.

The exhibit was to be open to the public at Hebrew University’s Jewish National & University Library, June 18-July 19. A digital version of the manuscripts can be seen online at: www.jnul.huji.ac.il/dl/mss/newton/.

Newton’s papers were first auctioned in 1936 and eventually ended up with British economist John Maynard Keynes, whose collection went to King’s College in Cambridge, England, and with Middle Eastern scholar Abraham Shalom Yahud, who bequeathed his collection to Israel upon his death in 1951.

Since 1969 the collection has been stored at the Jewish National & University Library, which serves as Israel’s national library, and although details of the manuscripts were made known in 2003 they were available only to a small number of scholars until now.