(This is the first story in a series looking at diocesan reconfigurations through parish closings and mergers.)

CLEVELAND – Just about every Sunday for the last dozen years, Pat Korcheck makes a 24-mile trek from her comfortable home in suburban Mentor to St. Cecilia Church in Cleveland’s Mount Pleasant neighborhood for 9:30 a.m. Mass. She always makes sure to leave early enough to pick up a couple of friends in Mount Pleasant so they can worship as well.

At most, she’ll do it for 12 months more.

The parish she has called home for much of her life is one of 27 in Cleveland – and 67 across the diocese – being closed or merged by June 30, 2010, under a plan recently announced by Bishop Richard G. Lennon.

Korcheck and many of her fellow parishioners are upset about losing their spiritual home. They are concerned that it appears the church is abandoning a long-struggling neighborhood.

While Korcheck understands that some parishes across the diocese should close, she said that closing St. Cecilia, a racially mixed Catholic community, and two other predominantly black Catholic parishes nearby sends the wrong message to black Catholics on Cleveland’s east side. She said as much in a letter to Bishop Lennon days after the closing was announced March 15.

“I said the Mount Pleasant community is being orphaned by the Diocese of Cleveland,” Korcheck said. “I think they’re devastating the inner city.”

She admitted that her concern arises out of Bishop Lennon’s decision to close St. Cecilia rather than merge the parish with another Catholic community under a new name.

In fact, a merger was recommended to the bishop late in 2008 after a 14-month series of meetings with Epiphany and Our Lady of Peace parishes, said St. Cecilia parishioner Fran Lissemore, a member of the committee which drafted the report.

Instead, Bishop Lennon opted to close – suppress in church parlance – St. Cecilia, keeping only Our Lady of Peace open.

In an interview with Catholic News Service, Bishop Lennon declined to discuss specifics of his decisions, some of which have upset Catholics across the diocese because they went against cluster committee recommendations.

However, Bishop Lennon, who arrived in Cleveland in 2006 after overseeing the closings and mergers involving 65 parishes in the Boston Archdiocese two years earlier, said his decisions were based on information gathered in parish self-studies as well as the need to ensure that diocesan resources, particularly priests, were being equitably distributed.

“It’s not just about downsizing,” he said. “That’s just a partial view of what we are about.”

Korcheck realizes the difficulty facing the Catholic Church in places such as Cleveland. “He’s in a bad position,” she said of the bishop.

The reality of changing demographics, declining parish revenues and fewer men in the priesthood are pressuring church leaders to realign church resources – parishes included – to best serve a Catholic community that is spreading across a much larger geographic area.

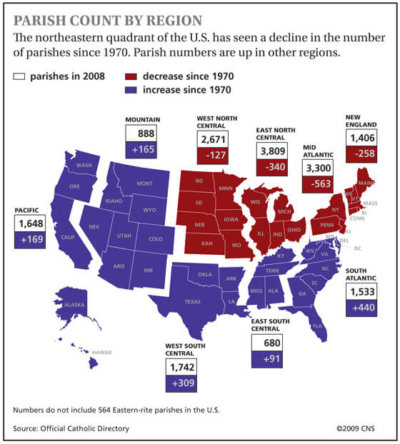

The downsizing trend largely affects churches in the Northeast and the Midwest. Disappearing are the days when parishes could be within walking distance of each other, each serving a different nationality.

On the other hand, in areas where the Catholic population is growing – primarily in the American West and in the Deep South – church officials are seeing burgeoning parishes. In some cases, new parish communities are being established.

In 2007 in the Archdiocese of Los Angeles for example, more than 95,400 infants were baptized in 287 parishes, according to the Official Catholic Directory. That’s an average of 332 children in each parish, or nearly one every day.

That contrasts with the pastoral life of some parishes being closed where less than 10 baptisms annually are the norm.

The list of dioceses experiencing closings and mergers in recent years is growing, according to Catholic News Service reports:

– Boston: 65 of 267 parishes closed or merged in 2004 and 2005.

– Camden, N.J.: 56 of 124 parishes to merge starting in 2009.

– New York: 10 parishes closed and 11 others merged in 2007.

– Syracuse, N.Y.: 36 of 173 parishes closed since 2006, with another 17 set to close as pastors retire.

– Allentown, Pa.: 47 of 151 parishes closed in 2008.

– Greensburg, Pa.: 15 of 100 parishes closed in 2008.

– Scranton, Pa.: more than 100 parishes closing or merging between 2008 and 2012.

Overall, data compiled by the Official Catholic Directory show that the number of parishes peaked in 1992 at 19,971. In the 2009 edition of the directory, which reflects information gathered in 2008, there were 18,674 parishes, a decline of 1,297 (6.5 percent) in 15 years.

The directory lists information only on the number of parishes and does not indicate how many actually closed and how many parishes opened in a given year.

Cleveland’s reconfiguration, under a program called Vibrant Parish Life that was introduced in 2001 by now retired Bishop Anthony M. Pilla, will leave the diocese with 174 parishes, down from 224 this year.

Bishop Lennon said the effort was necessary so the local church could better serve the needs of all 753,000 Catholics across the eight counties of the Cleveland Diocese.

“The key is mission to this whole thing,” he told Catholic News Service.

“It’s all based on a new understanding of what it means to be church,” the bishop explained. “To be church means that one is faithful in adhering to the mandates that have been given to us by Jesus Christ.”

Bishop Lennon’s words echo the intentions of bishops in many areas of the country as they strive to build vibrant parishes in an effort to boost Mass attendance and keep people engaged in parish life.

In Camden, N.J., diocesan spokesman Andy Walton said the 56 parishes that are merging are doing so to help carry out the desires expressed by more than 8,000 parishioners during a series of 140 “speak up” sessions that Bishop Joseph A. Galante called in 2005, a year after he was installed.

The sessions identified a number of goals – reaching out to teenagers and young adults to keep them engaged in the church, strengthening adult faith formation, promoting vocations to the priesthood, increasing opportunities for lay ministry, good liturgy and “compassionate outreach” to poor and marginalized people – as indicative of a healthy local church, Walton said.

“He (Bishop Galante) didn’t begin the listening sessions with the expectation that we would be engaged in a reconfiguration,” Walton told CNS. “The listening took place first. After listening to people he was able to see what the needs were and what the challenges were and he determined that action could no longer be deferred.

“It’s not simply that you look at parishes that are struggling and say, ‘Do something about them,’“ Walton added. “You look at each area of the diocese and say, ‘How can you improve parish life?”

Even as the frequency of parish suppressions and mergers increases, the Catholic Church in America remains strong, said Marti Jewell, the outgoing director of the Emerging Models of Pastoral Leadership, a 6-year-old collaborative effort between six national organizations studying the changing structure of parishes.

The organizations include National Association for Lay Ministry, Conference for Pastoral Planning and Council Development, National Association for Church Personnel Administrators, National Association of Diaconate Directors, National Catholic Young Adult Ministry Association and National Federation of Priests Councils.

Jewell called the current trend that is emerging – fewer parishes, fewer priests and greater involvement of lay leaders – “the most amazing paradigm shift” in the history of the U.S. Catholic Church. She said the shift is a natural evolution four decades after the Second Vatican Council.

“I think that what we’re being asked to do is to redefine our understanding of what a parish is,” she explained. “We know canonically what it is and I’m not talking about that. But what a parish does and who does it in a parish, I think we’re going to have to re-look at that. I think the spirit is inviting us deeply to seeing the parish as a community of disciples whose task is to evangelize the mission in the world.”We are where we are,” Jewell said. “There is no going back.”