By Maria Wiering

Twitter: @ReviewWiering

ANNAPOLIS – Vicki Schieber, 68, grins when she talks about her daughter – her intelligence, her beauty, her selflessness.

Her face softens when she talks about her murder.

Shannon Schieber was 24 when she was raped and murdered in her Philadelphia apartment. It was May 7, 1998, three days before Mother’s Day.

It took police four years to find the perpetrator, Tony Graves, who had raped several other women by the time he was apprehended in Colorado. Shannon was the only one he killed.

Graves was sentenced to life without the possibility of parole, not the death penalty, although Pennsylvania is one of 33 states that allow capital punishment.

The sentence satisfied Schieber, a vocal death penalty opponent. Even before Graves was caught, she forgave him, she said. She had seen hate and vengeance rip apart other families, and did not want that for herself.

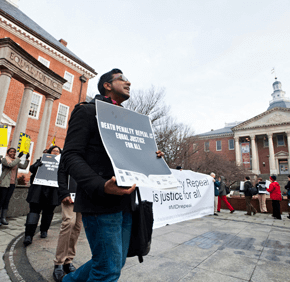

A parishioner of St. Peter the Apostle in Libertytown, Schieber was among dozens of activists who gathered Jan. 28 outside the Maryland State House to rally against Maryland’s death penalty.

For years, death penalty repeal advocates have been working to abolish capital punishment in the state, which could happen during the 2013 Maryland General Assembly.

Gov. Martin J. O’Malley led efforts to repeal the death penalty in 2009, and has thrown his support behind them again this year. Senate President Thomas V. Mike Miller, a death-penalty supporter, said he will ensure that repeal legislation makes it from committee – where the bill has languished in recent sessions – to a full chamber vote, if the governor can show there are enough votes in the Senate for approval.

Repeal advocates think they have the support of both the House and Senate.

Among them is the Maryland Catholic Conference, which advocates for public policy on behalf of the state’s bishops.

Support for death penalty repeal stems from the church’s pro-life teachings, said Bishop Denis J. Madden, an auxiliary bishop of Baltimore, who met with lawmakers to discuss the issue in January. Bishop Madden and Schieber sat on the 2008 Maryland Commission on Capital Punishment. After a series of hearings, the commission recommended abolition of the death penalty in its final report to the legislature.

Among the commission’s findings were that the death penalty is subject to racial and jurisdictional bias, more costly for the state than cases seeking life without parole, and inflicts misery on victims’ families.

Archbishop William E. Lori wrote a letter to Gov. O’Malley in December urging him to support death penalty repeal this year, and he plans to testify Feb. 14 during hearings on the issue in both the House and Senate.

The MCC is a member organization of Maryland Citizens Against State Executions, or CASE, a Mount Rainier-based coalition. Jane Henderson, its executive director, told rally attendees that 2013 is going to be “a historic year,” but that there is still much work to be done.

“We need to be sending a clear message that the majority of Marylanders are ready to abandon the death penalty and let life without parole be the maximum sentence,” she said through a megaphone.

A recent poll by Annapolis-based Gonzales Research shows 61 percent of Marylanders find life without parole an acceptable alternative to the death penalty; 33 percent find it unacceptable.

Not all Catholics believe the death penalty should be overturned. A national Pew Research Center poll released in 2012 found that 59 percent of Catholics support the death penalty for convicted murderers and 36 percent oppose it. With the exception of black Protestants, majorities of major U.S. religious groups favor the death penalty, according to the poll.

‘Non-lethal’ means encouraged

Church teaching grants that public authorities have the right and duty to punish criminals with penalties “proportionate with the gravity of the offense,” according to the Catechism of the Catholic Church – including the death penalty, “if this is the only possible way of effectively defending human lives against the unjust aggressor.”

However, “if non-lethal means are sufficient to defend and protect people’s safety against the aggressor, authority will limit itself to such means,” the Catechism states, “as these are more in keeping with the concrete conditions of the common good and are more in conformity with the dignity of the human person.”

It adds that cases where the death penalty is warranted today “are very rare, if not practically non-existent” given “the possibilities which the state has for effectively preventing crime, by rendering one who has committed an offense incapable of doing harm.”

St. Lawrence, Jessup, parishioner John Meinhardt know this. He has read the Catechism cover to cover, but is concerned that repealing the death penalty will not lead to justice for murder victims in Maryland.

The seriousness of a death penalty sentence demonstrates the value of the victim’s life, said Meinhardt, a longtime letter writer to the Catholic Review. To lessen the punishment is to devalue that life and not apply justice, he contends.

He would like to see the church turn more attention to homicide victims as part of its pro-life stance, he added. According to the Federal Bureau of Investigation, 14,612 people were murdered in the U.S. in 2011, the last full year for which data is available. By comparison, 42 men and women were executed via the death penalty in the same year.

Five years ago, Meinhardt’s work supervisor was murdered by her 28-year-old daughter. He was the first witness to testify at the trial. The daughter was found guilty and sentenced to life imprisonment without parole.

Meinhardt said he accepts life without parole as an alternative to the death penalty, if the sentence can be taken at face value. Living for decades in prison might be a fate worse than death, he reasoned. However, he points to instances of sentence reconsideration, where a judge reviews and sometimes reduces an inmate’s sentence.

In Maryland, an offender for any crime can file a petition within 90 days of sentencing to seek sentence modification, which is rarely granted to offenders with sentences of life without parole, Henderson said – so rare that she likens it to snow in July.

“The odds are so miniscule,” she said. “Life without parole is what it means.”

As for justice, Bishop Madden leaves “what’s due” to a person to God, he said. Anything more is vengeance, he said: “An eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth, and I think Christ moves us beyond that.”

A clinical psychologist, he said the data show that the death penalty does not deter violent crime.

“People just don’t think along those lines when they’re committing these things,” he said.

Scott Shellenberger, Baltimore County’s State Attorney, also served on the 2008 death penalty commission, but authored the minority report in support of keeping the death penalty “on the books” as an appropriate sentence for particularly heinous crimes.

“Look at what’s happened in our country in the past few years: Virginia Tech; Aurora, Colorado; Newtown, Connecticut,” he said to the Catholic Review. “In the face of that, do we really want to say that no one should face the death penalty again?”

The sentence also deters an inmate from killing a correctional officer, he said – a claim death penalty opponents often seek to refute, pointing to studies showing that people sentenced to life in prison without parole are less likely to break prison rules.

Maryland’s most recent execution occurred in 2005. Wesley Baker was killed by lethal injection, despite a plea for clemency from then-Archbishop of Baltimore Cardinal William H. Keeler, who visited Baker a week before his execution.

Today, five men in Maryland sit on death row at North Branch Correctional Institution, a super-maximum security prison near Cumberland.

Defending life

Executions in the state have been suspended since 2006 due to invalid lethal injection protocols. In 2009, the General Assembly strengthened evidence requirements for a death penalty sentence, resulting in the “tightest death penalty restrictions in the country,” according to the Washington, D.C.-based Death Penalty Information Center.

Cardinal Edwin F. O’Brien, archbishop emeritus of Baltimore, said in testimony before the 2008 commission that he once supported the death penalty, but had a “moment of conversion” after hearing Pope John Paul II preach against the measure in 1999. A defense of life from conception to natural death is part of the pope’s 1995 encyclical “The Gospel of Life.”

Repeal advocates point to an imperfect system, one that can wrongly convict an innocent man. Such was the now infamous case of Kirk Bloodsworth, a Marylander who was convicted in 1985 of the rape and murder of a 9-year-old girl. Nine years later, Bloodsworth became the first U.S. death-row prisoner to be exonerated by DNA testing.

He is now the director of advocacy at Witness to Innocence, a Philadelphia-based organization that supports people who have been exonerated from death row, 142 Americans since 1973.

Shellenberger said that Maryland’s new strict evidence standards would protect a case like Bloodsworth’s from conviction and the death penalty. He wished Marylanders understood how “careful the process is,” Shellenberger said.

“Even if the case is upheld on appeal, courts after courts are going to examine the proceedings to make sure that everything was done fairly and properly,” he said.

Bloodsworth is not convinced. He said that nothing can ensure that an innocent man could not be wrongly accused.

A Catholic convert while in prison, Bloodsworth, 52, points to Jesus as the prime example of an innocent person condemned to death.

“We cannot walk over an innocent man to execute a guilty man,” he said. “We need to think of the least of our brethren.”

Bloodsworth briefly shared his story at a lobbying event for death penalty repeal advocates following the Jan. 28 rally. Preparing to speak with their legislators were parishioners of St. Vincent de Paul and St. Matthew, both in Baltimore.

Pat Cassidy, 27, a Jesuit Volunteer Corps staff member who attends St. Matthew, said he has long opposed the death penalty, a conviction strengthened by his year-long correspondence with a Pennsylvania death-row inmate named Jimmy. The two write about once per month, and recently spoke on the phone for the first time.

Rather than focus on his pen pal’s culpability, Cassidy said his Catholic faith compels him to look to the possibility of redemption.

The death penalty “doesn’t allow for any opportunity for change within the individual, and that process of healing for themselves and of personal growth,” he said. “I don’t think that killing another individual brings about justice. It totally diminishes what we’re trying to work for and work towards – greater peace and love.”

Related articles:

Governor, NAACP push death penalty repeal in Maryland

Copyright (c) Feb. 4, 2013 CatholicReview.org