WASHINGTON – Jeanne Woodford looks forward to the day when no one will have to do what she did four times: plan and carry out an execution.

“They all weigh on me, as they do on everyone involved,” said Woodford, a former warden of San Quentin State Prison and now executive director of the national organization Death Penalty Focus, in a June 28 telephone interview with Catholic News Service from her San Francisco office.

Although her upbringing as a Catholic prompted her moral opposition to capital punishment, she is working to bring it to an end for several “more practical” reasons, she said. “It’s ineffective, it’s costly and it does so much harm to everyone involved.”

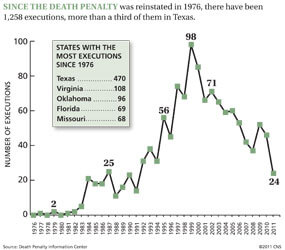

July 2 marked the 35th anniversary of the reinstatement of the death penalty by the U.S. Supreme Court, which said in Gregg v. Georgia that capital punishment is not inherently “cruel and unusual punishment” in violation of the Eighth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, as long as certain sentencing procedures are followed.

Since that 1976 decision, 1,258 people have been executed, according to the Washington-based Death Penalty Information Center. More than 3,200 remain on death row, including 713 people in California.

But according to a new report, the system in the United States remains as just as arbitrary today as it was when the death penalty was put on hold in 1972, when Justice Potter Stewart said capital punishment was “cruel and unusual in the same way that being struck by lightning is cruel and unusual.”

In the report titled “Struck by Lightning,” Richard C. Dieter, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center, said, “Many factors determine who is ultimately executed in the U.S.; often the severity of the crime and the culpability of the defendant fade from consideration as other arbitrary factors determine who lives and who dies.”

The major factors “in who receives the ultimate punishment” are race, geography “and the size of a county’s budget,” Dieter said. “Many cases thought to embody the worst crimes and defendants are overturned on appeal and then assessed very differently the second time around at retrial. … In such a haphazard process, the rationales of deterrence and retribution make little sense.”

The report compares the stories of several notorious murderers who did not receive the death penalty with the stories of some people who were executed.

For example, “Green River Killer” Gary Ridgway, who pleaded guilty to 48 murders in 2003 in Washington state, was spared the death penalty because of information he provided about the women he had killed. Oscar Veal, convicted of seven counts of murder and eight counts of racketeering as part of a large drug and murder-for-hire organization, received only a 25-year sentence because of his cooperation with authorities in the District of Columbia. Serial killer and sex offender Jeffrey Dahmer received 15 consecutive life sentences for 15 murders in Wisconsin, which does not have the death penalty. (In 1994 Dahmer was beaten to death by a fellow inmate.)

On the other hand, among those executed over the past 35 years was Manny Babbitt, a Vietnam veteran suffering from post-traumatic stress symptoms who beat an elderly woman who died of a heart attack. Babbitt was executed in 1999 in California, shortly after receiving the Purple Heart in prison. Dieter also cites cases in which the executed were mentally ill, intellectually disabled or later exonerated of the crime for which they were killed.

“Thirty-five years of experience have taught the futility of trying to fix this system,” he wrote. “Many of those who favored the death penalty in the abstract have come to view its practice very differently. They have reached the conclusion that if society’s ultimate punishment cannot be applied fairly, it should not be applied at all.”

Advocates like Dieter and Woodford know they have their work cut out for them.

Although four states have abolished the death penalty in the past four years, public opinion polls still show a great deal of support.

In a Rasmussen Reports national survey released June 29, 63 percent of American adults said they favor use of capital punishment, while 25 percent opposed it and 12 percent were undecided.

Less than half (47 percent) of the respondents believe the U.S. system of justice is fair to most Americans, 34 percent believe it is not fair and 19 percent are undecided. But by a margin of 64 percent to 19 percent, Americans believe the bigger problem for U.S. law enforcement is that too many criminals are set free rather than that too many innocent people are arrested. The remaining 17 percent were undecided.

The margin of error for the survey of 1,000 adults, conducted June 25-26, was plus or minus 3 percentage points.

In these tough economic times, however, death penalty opponents believe that Americans have good fiscal reasons to join their cause.

A new study by U.S. 9th Circuit Judge Arthur L. Alarcon and Loyola Law School professor Paula M. Mitchell found that taxpayers have spent more than $4 billion on capital punishment in California since 1976 – or about $308 million for each of the 13 people executed in the state since that time.

Their report, titled “Executing the Will of the Voters: A Roadmap to Mend or End the California Legislature’s Multi-Billion Dollar Death Penalty Debacle,” measured state, federal and local expenditures for capital cases – including enhanced security on death row, legal representation for the condemned and additional costs of capital trials – and concluded that capital punishment adds $184 million to the budget each year.

Woodford’s 28 years at San Quentin and a brief stint as head of the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation have convinced her that although some prisoners may need to be kept away from society for the rest of their lives, killing them is not the answer.

“We have a system that isn’t functioning for anyone and that is wasting resources we could be using to put more teachers in the classroom,” she said.