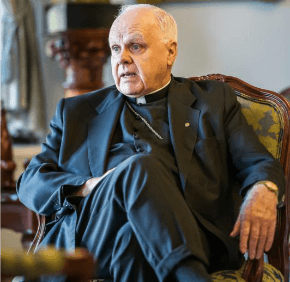

Editor’s note: This article about Cardinal Edwin F. O’Brien, archbishop emeritus of Baltimore and grand master of the Equestrian Order of the Holy Sepulcher of Jerusalem, was written prior to the Nov. 14 terrorist attacks in Paris. Since then, he has been named by the Vatican as a member of the Congregation of Saints’ Causes.

By Sharyn McCowen

Special to the Catholic Review

SYDNEY – When Cardinal Edwin O’Brien was named grand master of the Equestrian Order of the Holy Sepulcher of Jerusalem in 2012, he found himself embroiled in a war a world away from the jungles of Vietnam where he ministered to dying troops as a young priest.

“The forces that are at work now are intent on eradicating the Christian civilization, nothing less, nothing less,” said the 76-year-old archbishop emeritus of Baltimore. “It’s genocide taking place.”

In Sydney last month to reach out to the Equestrian Order’s 600 Australian members, Cardinal O’Brien didn’t pull his punches in relaying the daily horror faced by Christians in the Holy Land.

“I think our public is very blasé about the whole thing,” he told The Catholic Weekly, newspaper of the Archdiocese of Sydney.

“We’re afraid to say that this is an extremist terrorist group that is basing their principles falsely on the tenets that they believe are theirs from God himself.

“Unless we face the facts, this radicalism, this extremism, is going to keep spreading.”

Most disturbing for Cardinal O’Brien is the lack of military response from the United States.

“We’ve had an opportunity to stop those forces,” he said.

Islamic State fighters attacked 35 Assyrian villages on the Khabur River in Syria in February, killing a dozen people, kidnapping more than 90 Assyrian Christians, burning two churches, and forcing more than 3,000 people to flee.

“We did nothing to stop them,” he said.

“And now those Christian villages have been eradicated, (people) killed, taken into slavery.

“What have we done about it?”

The inaction from the United States was particularly grievous for Cardinal O’Brien who has spent much of his life working alongside its military.

Born and raised in the Bronx, he was ordained a priest of the Archdiocese of New York in 1965 as the United States Military Academy at West Point was preparing to double in size.

The young priest was appointed to the academy, initially as a civilian priest on a temporary posting.

That posting stretched to five years and he was so impressed by the tenacity shown by a generation of young men that he could no longer remain on the sidelines.

“I’d be marrying cadets in June, and a year later burying them, because they had been shipped right to Vietnam,” he said. “I had great admiration for what I saw and what I heard: the generosity, the integrity, the selflessness of the cadets and of the staff.

“It was almost a continuation of my formation as a priest, the example I received.”

He joined the U.S. Army with the rank of captain with one goal in mind.

“I’d been promised I could go to jump school, airborne training, and I could go to Vietnam, because that’s what I wanted to do.”

His mission, as he saw it, was clear: “To keep our men and women in the military strong in their faith, and to give them guidance and counsel when they needed it personally or professionally.”

To serve alongside troops in combat was the first step toward gaining their trust, the cardinal said.

“I think one gains greater credibility when one shares the burden, in any way of life.

“The fact that chaplains – whether they were a priest, a minister or a rabbi – would travel halfway around the world not out of any self-interest but to serve, and to bring into a very challenging situation for these young people, meant a great deal to them.”

Despite witnessing grave losses and suffering, the experience reinforced rather than challenged his faith.

“It was a strengthening of my faith, because I saw the role of the military, as I do now, to be a very lofty vocation.

“Christ said, ‘I have come to serve and not be served.’ When one puts on a uniform that person enters the service.

“ ‘Greater love has no one than this, to give his life for his friends.’ ‘Peace I leave with you, my peace I give you.’

“What is the military for – a good military, a noble military – but to bring about peace?”

Decades later, another war defined another chapter of his priesthood as he asked that question of an entire nation.

In September 2011 he was four years into his tenure as Archbishop for Military Services in the United States, overseeing the nation’s 1.5 million serving Catholics, when the country was struck by four terrorist attacks.

“I was at my desk in Washington on Sept. 11,” he said.

The military ordinariate had been hosting a retreat for 40 Washington priests who were chaplains to local military units.

“I heard of the first plane, then I rushed over to where the chaplains were, and everything was on lockdown.

“All these chaplains were from the Washington area. They couldn’t move; they couldn’t get back to their units.

“It was a traumatic moment, and everyone looked to the military to do something and to the president to take action, and the president was more than willing to do it.”

As the United States prepared for massive military intervention in Iraq, Cardinal O’Brien drew public and media scrutiny when he appeared to endorse the invasion in the context of Just War doctrine.

In 2003 Cardinal O’Brien told a congregation of servicemen at a Mass at West Point: “I know that a lot of people have said that the pope is against war with Iraq. … But even if he did, you are not bound by conscience to obey his opinion. However, you are bound in conscience to obey the orders of your commander-in-chief, and if he orders you to go to war, it is your duty to go to war.”

In March that year he wrote to U.S. Catholic military chaplains: “Given the complexity of factors involved, many of which understandably remain confidential, it is altogether appropriate for members of our armed forces to presume the integrity of our leadership and its judgments, and therefore to carry out their military duties in good conscience (nota: “our leadership” is not referring to the pope). … It is to be hoped that all factors which have led to our intervention will eventually be made public, and …will shed helpful light upon our president’s decision”.

Speaking to The Catholic Weekly, he said: “It was discussed in the press not because a Catholic bishop posed the question, but because Just War theory is a natural law, a set of principles that dates back 1,500 years to St Augustine.”

“I spoke out about that, raised some questions that our government should answer.”

While the Military Ordinariate does not set policy, “we tell those who are responsible for setting policy and carrying out policy what answers they should be required to give if they’re going to justify the increased action in the Middle East”

“We were just bringing that to the fore and saying, ‘Whether you’re religious or not, whether you’re Catholic or not, when it comes to taking other lives there has got to be some very serious thought and debate and conscientious conclusions to be reached.’

“These are the questions that have to be answered.”

On a personal level, it is a question that prompts reflection from military personnel of any faith.

“I saw my role as (being) to remind our military, Catholics especially, that there is no contradiction between what they do when they put that uniform on, as long as they do it in good faith and according to the principles of Catholic ethics.”

While his contemporaneous comments saw him labelled the ‘Warrior Cardinal,’ he never wavered from advocating the importance of chaplains at a time when the proportion of Catholic chaplains, just eight percent, was vastly outnumbered by the 27 percent of U.S. military who identified as Catholic.

Cardinal O’Brien left the military archdiocese in 2007 when he was appointed Archbishop of Baltimore.

His appointment as grand master of the Equestrian Order of the Holy Sepulcher of Jerusalem came as a shock after less than four years in Baltimore, a posting he believed would be his last.

“I thought I would die in Baltimore,” he said. “I got there within seven years of retirement and I just presumed that was the last stop. When I got the call I didn’t want to leave, but when the Holy Father asks you to do something you do it.

“That’s been my mantra for others, and it’s a mantra I had to carry out myself.”

Three years on, the cardinal said he enjoys “the challenge of serving some very generous men and women – 30,000 knights and ladies of the Holy Sepulcher – who are intensely interested in bringing justice and relief to a downtrodden minority in the Holy Land.”

“To serve them and to encourage them is to serve some of the poorest in the world, and some of the most persecuted Christians.

“It’s a great responsibility to join the order, a responsibility to serve our fellow Christians in the Holy Land through an effective organisation such as ours.”

In 50 years of priesthood, Cardinal O’Brien has devoted more than a dozen to work in seminaries.

“Vocations – especially to the priesthood – have always been a preoccupation of mine,” he said.

“Even when I was archbishop of the military, our hope was, and we had some success, in having men come out of the military with a changed attitude, a stronger sense of self-giving, and enter the seminary.

“And I would hope that in Australia and throughout the western world that the shortage of vocations will soon be resolved.”

He was confident Pope Francis’ recent visit to the United States would spark a renewed interest in religious life.

“He visited the United States and each of the former visits by Holy Fathers to our country has encouraged fuller seminaries. And I think that’s going to happen in our case.”

Also see:

Knights of Columbus sponsors CRS to help educate Middle Eastern refugees

Nothing can justify terrorist attacks, pope says