VATICAN CITY – Pope Benedict XVI said he would go to Assisi in October to mark the 25th anniversary of Pope John Paul II’s interreligious prayer for peace, but he did not actually say anything about praying with members of other religions.

Announcing the October gathering, he said he would go to Assisi on pilgrimage and would like representatives of other Christian confessions and other world religions to join him there to commemorate Pope John Paul’s “historic gesture” and to “solemnly renew the commitment of believers of every religion to live their own religious faith as a service in the cause of peace.”

While Pope Benedict may be more open to interreligious dialogue than some of the most conservative Christians would like, he continues to insist that dialogue must be honest about the differences existing between religions and that joint activities should acknowledge those differences.

In the 2003 book, “Truth and Tolerance,” a collection of speeches and essays on Christianity and world religions, the then-Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger dedicated four pages to the topic of “multireligious and interreligious prayer.”

As a cardinal and prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, he was one of the very few top Vatican officials to skip Pope John Paul’s 1986 meeting in Assisi. He later said the way the event was organized left too much open to misinterpretation.

His chief concern was that the gathering could give people the impression that the highest officials in the Catholic Church were saying that all religions believed in the same God and that every religion was an equally valid path to God.

A few years later – and after having participated in Pope John Paul’s 2002 interreligious meeting in Assisi – he wrote in “Truth and Tolerance” that with such gatherings “there are undeniable dangers and it is indisputable that the Assisi meetings, especially in 1986, were misinterpreted by many people.”

He wrote that church leaders had to take seriously the possibility that many people would see Jews, Christians, Muslims, Buddhists, Sikhs, Hindus and others gathered together for prayer in the Umbrian hilltown and get the “false impression of common ground that does not exist in reality.”

At the same time, he said, it would be “wrong to reject completely and unconditionally” what he insisted was really a “multireligious prayer,” one in which members of different religions prayed at the same time for the same intention without praying together.

In multireligious prayer, he wrote, the participants recognize that their understandings of the divine are so different “that shared prayer would be a fiction,” but they gather in the same place to show the world that their longing for peace is the same.

U.S. Jesuit Father Thomas Michel, who was an official at the Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue in the 1980s and was involved in organizing the first Assisi meeting, said, “It wouldn’t make a lot of sense to pray together when you don’t believe in the same God,” but Catholics believe there is only one God and he hears the prayers of whoever turns to him with sincerity and devotion.

In an e-mail response to questions, Father Michel said, “The only confusion (surrounding the 1986 Assisi meeting) was among those who did not understand Vatican II teaching and subsequent magisterium. They expressed their confusion before the event, boycotted the event itself, and expressed more confusion afterwards.”

“Nostra Aetate,” the Second Vatican Council document on relations with other religions, affirmed that Jews, Christians and Muslims believe in, worship and pray to the same God.

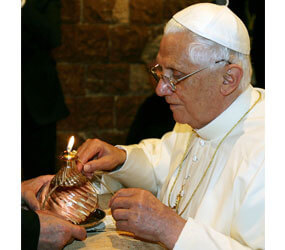

When Pope Benedict went to Istanbul’s Blue Mosque in Turkey in 2006, some people believed he blatantly contradicted what he had written in 2003 about the impossibility of praying together.

At the mosque, a place of prayer for Muslims, the pope stood alongside an imam in silent prayer.

Days later back at the Vatican, the pope said it was “a gesture initially unforeseen,” but one which turned out to be “truly significant.”

“Stopping for some minutes for reflection in that place of prayer, I turned to the one God of heaven and of earth, the merciful father of all humanity,” the pope said.

Muslims were touched by the pope’s gesture, but some Christians went to great lengths to insist that the pope’s “turning to God” was not the same thing as prayer, especially in a mosque.

People found it easier to accept the fact that Pope Benedict stopped for prayer in Jerusalem at the Western Wall, Judaism’s holiest site.

After visiting Jerusalem, Pope Benedict told visitors at the Vatican that faith demands love of God and love of neighbor; “it is to this that Jews, Christians and Muslims are called to bear witness in order to honor with acts that God to whom they pray with their lips. And it is exactly this that I carried in my heart, in my prayers, as I visited in Jerusalem the Western or Wailing Wall and the Dome of the Rock, symbolic places respectively of Judaism and of Islam.”

In a message commemorating the 20th anniversary of Pope John Paul’s Assisi meeting, Pope Benedict said the 1986 gathering effectively demonstrated to the world that “prayer does not divide, but unites” and is a key part of promoting peace based on friendship, acceptance and dialogue between people of different cultures and religions.