By Maria Wiering

mail@CatholicReview.org

Cinthia, an immigrant who lives in Baltimore, anticipated an April phone call confirming her two daughters, ages 9 and 12, had made it to the United States from Honduras.

When the call came, she couldn’t have anticipated additional news: 9-year-old Gelen had suffered a stroke.

“I was very scared. I was screaming a lot,” Cinthia said.

From the caller – another immigrant who had accompanied her daughters – Cinthia learned that Gelen felt ill before the U.S.-Mexico border crossing. She struggled to walk, so someone carried her. Soon after they were on the U.S. side, the girls were taken into custody by U.S. immigration officials and put in a truck.

Inside, Gelen blacked out.

Finding help

By the time her mother received the news, Gelen (pronounced “Helen”) was in a Texas hospital. Her sister, Maria Belén, was in an immigration detention center.

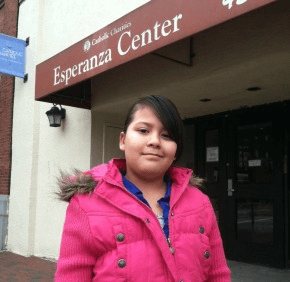

Maria Belén eventually joined her mother in Baltimore as part of the U.S. Office of Refugee Resettlement’s family reunification program. Gelen, however, remained hospitalized, unable to reunite with her mother because she needed medical care. For help, Cinthia, 31, leaned on relatives and reached out to Catholic Charities of Baltimore’ Esperanza Center, where she had been fingerprinted as part of the reunification process.

Cinthia, who asked that her last name not be printed, recounted her story in Spanish. Jermín Laviera, an Esperanza client services representative who worked with Cinthia and her daughters, translated for the Catholic Review on her behalf.

Esperanza’s staff members and nursing student volunteers from the University of Maryland connected Cinthia with specialists from Johns Hopkins Community Physicians, who committed to continuing Gelen’s specialized care. Securing that commitment was critical for Cinthia to obtain approval as Gelen’s sponsor and in reuniting mother and daughter, according to Val Twanmoh, Esperanza’s director.

In June, Gelen was transferred from Texas to a medical facility in Albany, N.Y., where she continued her recovery and received visits from her mother and sister.

After two more months of therapy, the facility discharged Gelen, and Cinthia took her home to Baltimore Sept. 11.

Now 10, Gelen is enrolled in school and continues therapy at Johns Hopkins’ East Baltimore Medical Center, which charges for medical services on a sliding scale.

Hope for recovery

After Cinthia’s parents died, she left Colon, Honduras, about three years ago seeking work to support her family. Her daughters stayed in Honduras with their stepfather, but he moved the girls to different houses and stole the money Cinthia sent for their care, she said. Escalating violence and risk of kidnapping in Honduras compelled her girls’ 20-day journey north.

Gelen sat quietly as she listened to her mother recount her family’s story. “Hello” is one of the few words she can say again. Her right side remains partially paralyzed. Cinthia is hopeful her daughter will make a full recovery.

A parishioner of Sacred Heart of Jesus-Sagrado Corazón de Jesús in Highlandtown, Cinthia looks to her relatives and God for support, she said.

“Cinthia’s was a hard case,” said Laviera, the Esperanza Center translator, adding that the family’s outcome makes her “feel very, very happy.”

Most from Honduras

While youths from El Salvador, Guatemala and Mexico also contribute to the more than 67,000 immigrant minors who crossed the U.S.-Mexico border illegally last year without guardians, most are from Honduras, according to U.S. Customs and Border Protection.

Through the Office of Refugee Resettlement, many unaccompanied minors are able to reunite quickly with family members already living in the U.S.

In 2014, Esperanza reunified 481 unaccompanied minor children with family members. The Fells Point center is one of two places in Maryland where people can be fingerprinted as they work to gain custody of unaccompanied minors who have crossed the border.

Pope Francis has called the surge of unaccompanied minors crossing the U.S.-Mexican border a “humanitarian emergency” and has asked for them to be “welcomed and protected.”

In August, Catholic Charities of Baltimore applied for a federal grant to house unaccompanied minors as they wait to be reunified with family members. It learned in early December that the Office of Refugee Resettlement has deferred a final decision on the proposal, as it “has adequate capacity among its current shelter providers to meet the current need for transitional shelter services,” Catholic Charities Executive Director William J. McCarthy Jr. wrote in a Dec. 9 e-mail to the agency’s staff that was forwarded to the Catholic Review.

Also see: