VATICAN CITY — Going out to the “peripheries” may be a phrase favored by Pope Francis, but even in diplomatic affairs, it is something the Vatican has done for centuries, often in the face of danger.

As news of a possible agreement between China and the Vatican sparked debate about the best ways for the Catholic Church to deal with the Asian superpower, the Polish Institute in Rome recounted the story of a Polish Franciscan monk sent on a papal mission to the Far East 25 years before Marco Polo.

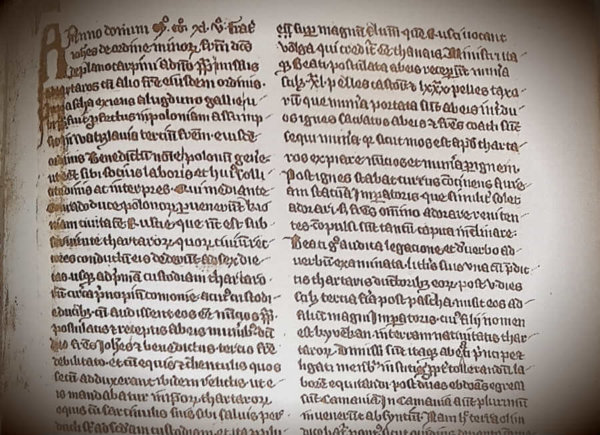

The amazing adventures of Benedict of Poland, a Franciscan who accompanied a papal diplomat to Mongolia in 1245, were the centerpiece of the institute’s exhibit in late February.

Benedict’s accounts of his journey give insight into the diplomatic protocols of the Holy See at the time, showing great openness to and respect for other cultures, Franciscan Father Emil Kumka told Catholic News Service March 1.

“They adapted to these customs. To complete their diplomatic mission meant that flexibility and openness to customs and culture” was very important and, besides, it was consistent with the spirit of St. Francis of Assisi, said the priest, who is a historian at Rome’s Pontifical University of St. Bonaventure.

Even though very little is known about his life, Benedict of Poland’s account sheds some light on the journey and gives a firsthand look at Mongolian life and culture with details not included in the official account of the journey written by Giovanni da Pian del Carpine, one of St. Francis of Assisi’s first companions and Pope Innocent IV’s choice as representative to the Mongols.

“The history of the Mongols written by Giovanni (da Pian del Carpine) is very well-known. Indeed, what isn’t well-known is the fact that this trip was made before Marco Polo and it was the first official encounter between the West and the Far East,” Father Kumka noted.

The diplomatic mission undertaken by Del Carpine and Benedict, he added, was no small feat given the fear and uncertainty that reigned in Europe during the 13th century after the Mongols’ first incursion into European territory in 1219.

Initially known in Europe as the Tartars, the Mongols were a people surrounded by legend. Yet, the myths turned into a horrifying reality when the Mongol prince and commander, Batu Khan, led several ferocious campaigns and eventually conquered Poland and Hungary.

With the threat of Mongolian rule looming across Western Europe, Europeans were given a chance to regroup their forces and learn more about their enemy after the Mongolians suddenly retreated.

Unbeknownst to the Europeans, news had reached Batu Khan of the death of Great Khan Ogedei, so Batu Khan immediately withdrew for the election of the next Mongolian leader.

The Mongol retreat prompted Pope Innocent to send del Carpine with a message to the Great Khan in the hopes of preventing a Mongolian attempt to conquer the entire European continent. The pope also charged his envoys with the mission of gathering intelligence on the Mongolian forces, and also of gauging the possibility of converting them to Christianity, according to the exhibit catalogue.

While del Carpine was the pope’s point man, Father Kumka said, he asked Benedict, whom he knew prior to the diplomatic mission, to join him.

“Benedict spoke Russian, Latin, Polish and most likely — although there are certain debates about this — he had a rudimentary knowledge of the Mongolian language,” Father Kumka explained.

Benedict had been imprisoned by the Mongols shortly after the invasion of Poland in 1241 and is believed to have acquired a basic understanding of their language.

The Franciscan travelers arrived at their destination one month prior to the election of Guyuk, the grandson of Genghis Khan, as the third Great Khan of the Mongol empire.

At a time when Europeans considered the Mongolians to be savages, mainly due to their prowess on the battlefield, del Carpine and Benedict wrote with surprise of the advanced diplomatic skills of the Mongols, as well as the pageantry of their festivities after Guyuk’s election.

“The legates of Pope Innocent IV blazed the trail and opened the European rulers’ eyes to the possibility of establishing contacts or even collaborating with exotic Asian countries,” according to the exhibit’s catalogue.

While del Carpine provided official documentation about the mission, Benedict’s account of the journey is a testament to the importance of those who work behind the scenes, Father Kumka told CNS.

“Benedict is an example of that service. Obviously, he didn’t pretend to be great because he helped Giovanni in this journey desired by the pope. And he left his little contribution written down,” he said. “The greats write history but the greats were always accompanied by secondary people and they are always unseen.”

Father Kumka added that passing on the story of a fellow Pole and a fellow Franciscan like Benedict of Poland “is a great joy.”

“As a historian, it is always important for me to recover these secondary figures. Because from the main figures, we know the stories,” Father Kumka said. “But we often forget those who were in their service and helped. Without these secondary people, the greats wouldn’t have been able to achieve anything.”

Copyright ©2018 Catholic News Service / U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops.