WASHINGTON — Modern society — largely defined by capitalism and consumerism, burgeoning technology, religious-like allegiance to nation and the rise in secularism — has its roots in the Protestant Reformation, says historian Brad S. Gregory.

And both are intertwined much more than a lot of people think, according to Gregory.

The Reformation can be traced to Oct. 31, 1517, when, the story goes, Augustinian friar Martin Luther posted his 95 theses on the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg, Germany.

That seminal event opened the way for communities across Europe to experience new understandings of the Bible, spawning political and religious conflicts and a cultural revolution that continues to shape the world, Gregory said.

“If you can’t understand the Reformation and what followed in its wake, you can’t understand the world that we’re living in today and why it is the way it is,” Gregory told Catholic News Service.

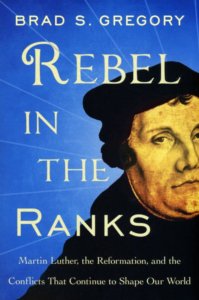

Gregory, a professor of early modern European history at the University of Notre Dame, examines the impact of Luther’s seemingly noble act in “Rebel in the Ranks,” published this fall as a nonacademic work for readers interested in history, the Reformation and understanding the world as it exists today.

“The thrust of the book is that the ironic overriding outcome of the Reformation, which sought to make society more Christian, and the Reformationists thought it was, ended up unintentionally in the long run secularizing society,” Gregory said.

He contends throughout the book that “things that happened 500 years ago are still affecting us.”

“But I think very few Americans would recognize that,” he said.

“Rebel” explores the events that led Luther to write his 95 theses, formally titled the “Disputation on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences.” Gregory writes that it is uncertain whether he actually posted the theses on the church door or sent them to the then-27-year-old archbishop of Mainz and Magdeburg, Albrecht von Brandenburg.

The book places Luther’s action within the context of the religious and political realities of early 16th-century Europe. He explores the allegiances between church leaders, including the pope in Rome, civic leaders and ruling families and how they shaped the Catholic Church as the Middle Ages were ending.

Gregory’s work explains that Luther was tormented by his desire to live according to established religious rules and thought others should too. Luther wrestled with what he saw were his failures to obey God; the more he struggled, the harder his struggles became. Gregory describes Luther as being in a “spiritual quicksand.”

A rather anonymous friar until writing his theses, Luther hardly saw himself as starting a revolution or undermining church authority, Gregory wrote. Even after Pope Leo X excommunicated him in January 1521, Luther continued to wear his Augustinian robes and lived in the friary in Wittenberg.

Following his theses, Luther developed a series of theological reflections on the nature of faith. His writings reinforced a central theme: “No one can be justified except by faith.” Gregory’s book explains that Luther held firm to the belief that nothing any single person does can make up for their sins in the sacrament of penance to receive Communion and that only trust in God’s promise of forgiveness can truly atone for sin. Luther’s personal spiritual struggles testify to that, Gregory writes.

That reasoning inspired millions across Europe. Luther’s impact grew immensely so that by the summer of 1521, he is perhaps the continent’s most famous man and its all-time best-selling author. Despite his popularity and kick-starting the Reformation, Gregory maintains that Luther never had control of the movement. As a result, it diverged into various Protestant denominations, leading to religious conflict, intermittent ethnic violence and wars across much of the European continent for decades.

“There is disagreement from the outset within Protestantism and, of course, disagreement between all types of Protestantism and those who remain Catholic,” Gregory told CNS.

With different beliefs, the Western world fragmented, and wars and conflicts resulted. The Thirty Years’ War, primarily fought in central Europe from 1618 to 1648, was fought over religion and resulted in 8 million deaths including a third of all Germans.

From such violence, allegiance to country became a substitute for allegiance to religion by the 19th century, Gregory explained. Such loyalty to country has become an ever more deeply held value today.

Further, as European explorers traveled the world in the 16th and 17th centuries, they exported their cultural and religious practices to new lands. Colonialism and imperialism grew for the next 300 years influenced the development of nations and saw geopolitical alignments, some of which continue into the 21st century. Today, Gregory said, the West’s influence, seeded in the colonial era, continues through media and technology and the constant drive by influential worldwide corporations to boost profits by creating demand to own new, and many, things.

The Reformation set in motion a world that Luther would likely reject today and seek to reform as he did the church in the 16th century, Gregory said.

“Christianity is not supposed to be separate from how power is to be exercised,” he said. “It is supposed to be part of life. (It’s supposed) to shape politics and how political leaders exercise power. So too with the family and institutions. The Christian message is supposed to be carried out. It’s supposed to limit appetite for stuff and profit.”

While Gregory’s book recounts the challenges facing an increasingly technology-based, consumerist society, he deliberately avoids offering solutions. That, he said, is the duty of people who envision a world that can be united through the observance of religious tenets that promise a just world.

“This book is about understanding,” he said. “This is not a book about how do we fix the problems.”

Also see:

Bishop Madden praises Lutheran-Catholic relations during Reformation program

Copyright ©2017 Catholic News Service/U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops.