ORLANDO, Fla. —In 1955 in Mississippi, a white woman lied and told her husband that Emmett Till, a black teen, flirted with her in the grocery story. In retaliation, her husband and another man kidnapped, beat, shot and lynched the youth.

His body was found three days after his murder and returned to his native Chicago. His mother had an open casket for the 14-year-old’s funeral, where tens of thousands visited his body. Among them were an 11-year-old Edward Braxton, his brother, Lawrence, and his uncle, Ellis. They waited two hours in line to view the body.

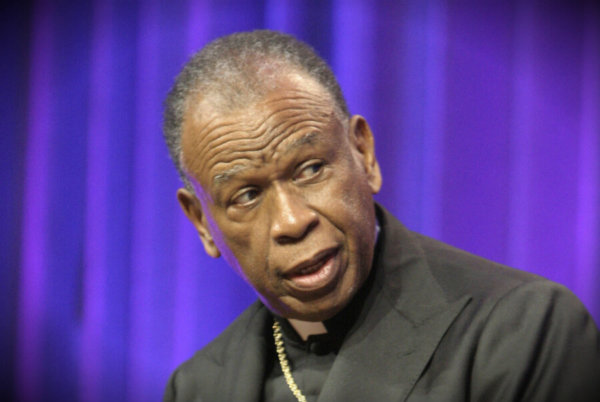

“I peered into the glass coffin and beheld the terrifying remains of a vicious murder,” said the now 73-year-old bishop of Belleville, Illinois. “He did not look like a human being. Emmett’s mother was sitting in a chair, uncontrollable crying, saying, ‘My baby. My baby. Why? Why did I send him down South. I looked into her red-rimmed eyes not knowing what to say.”

Uncle Ellis repeatedly told his nephews, “I don’t want you ever to forget this night.” And Bishop Braxton never did. Emmett’s killers were never convicted of murder. And when he visited the National Museum of African American History and Culture, he was transported to that day in 1955.

“For me personally, the most devastating experience in the history gallery was coming face-to-face with the original coffin of dear Emmett Till, which I had not seen in 60 years,” Bishop Braxton said during his keynote address July 8 at the National Black Catholic Congress in Orlando, adding that “dear Emmett Till” was one of 3,446 African-Americans lynched between 1882 and 1968.

“I have never forgotten (my uncle’s) words. I have never forgotten the unrecognizable bloated, totally mutilated face behind the glass in that coffin. … Seeing that coffin again brought it back again,” he said.

That was only one piece of history at the museum that registered great emotions for the bishop, who has written extensively on the racial divide in America from a theological and pastoral perspective.

Among his writings are two pastoral letters, “The Racial Divide in the United States: A Reflection for the World Day of Peace 2015” and “The Catholic Church and the Black Lives Matter Movement: The Racial Divide in the United States Revisited,” issued in 2016.

In his congress address, he described how the National Museum of African American History and Culture museum is in eyeshot of the monument to George Washington and the memorial to Thomas Jefferson, both of whom owned “enslaved free human beings.” Not too far away are the Capitol and the White House, both built in part by “enslaved free human beings,” as he put it.

The history presented at the museum is not pretty but so important, and he urged everyone to visit the museum, especially the lower levels.

“I realized 60 percent of the museum is actually underground and it is underground deliberately because the architect wanted to give you the feeling that you were … maybe inside a slave ship crowded with very little room to move about,” Bishop Braxton said.

“The images in the museum reminded me of what happened to free human beings as they crossed the Atlantic in the Middle Passage,” he continued. “Human beings chained side by side on top of one another in unspeakable squalor, cramped in darkness. … An estimated 2 million people lost their lives during the Middle Passage of this African holocaust.”

In January, he wrote an essay on the museum titled “We, Too, Sing ‘America’: The Catholic Church and the Museum of African American History and Culture.”

Although he recognized the museum as an outstanding achievement, Bishop Braxton in his remarks to the congress lamented the lack of references there to leading African-American Catholics such as Father Augustus Tolton, the Sisters of the of the Holy Family, Sister Henriette Delille, Father Pierre Toussaint, Mother Mary Lange, or Sister Thea Bowman at the museum. There are nearly 68 million Catholics in United States, but only 2.9 million are black.

“These absences reminded me that African-American Catholics then and now were already invisible in the larger influential black church,” Bishop Braxton said. “At the same time, African-Americans were and remain all but invisible in the larger influential and largely European-American Catholic Church.”

The bishop told congress attendees they could all do something to know their own history and to be engaged in the community. They must exercise their rights to vote, participate in public life, run for public life, use resources that develop discussion about the racial divide, inspire young people to become involved.

“I give you these imperatives: Listen, learn, think, act and pray,” he said. “African-American Catholics need to get into real conversations with others in the community about this history so we can grow by means of knowledge.”

Before closing, Bishop Braxton brought up a theme that he has “raised for years, to no avail” — that “people of color should no longer accept the designation of African-Americans as a minority. We are not a minority; we are Americans.” Referencing the words of the poet Langston Hughes, “We, too, sing America.”

“The word minority group is a term used to divide, not to unite,” he said. “The God who is God has no color, has no race, has dimensionality. It is so important that we depict the universality of the mission of God, showing diversity of the city of the kingdom of God.”

In his remarks, Bishop Braxton also spoke about the prophet Micah, known as the prophet of social justice, whose warnings and criticism of political corruption and urging of caring for the poor still ring true 2,700 years later. A passage by Micah provided the theme of the congress: “The Spirit of the Lord is upon me: Act justly, love goodness and walk humbly.”

The bishop said the prophet would not be satisfied with those words solely emblazoned on T-shirts, banners and bags.

“Micah would demand to see these words written in our hearts, in our daily actions when we leave Orlando and return to our dioceses, neighborhoods, parish communities and families,” Bishop Braxton said.

In talks a day earlier, Bryan Stevenson, a public interest lawyer, and Tricia Bent-Goodley, a professor and director of the doctorate program at Howard University School of Social Work, separately spoke about black communities, and the justice system and black family life.

Stevenson shared his work fighting mass incarceration, racial bias and poverty through the legal system. He founded the Equal Justice Initiative, which works to eliminate excessive sentencing, to exonerate innocent death-row inmates, and to challenge the abuse of the incarcerated and the mentally ill. Stevenson praised black Catholics for “raising their voice in support of social justice and all the commands of the Gospels.”

In speaking about “The Black Family: Challenges and Opportunities,” Bent-Goodley described the impact of mental health issues, community violence, and domestic violence on black families. She called on black Catholics to face these issues with both the power of prayer and the help of professionals.

She noted that too often, black families don’t get the care and counseling they need; sometimes because of a lack of access and sometimes because of a reluctance to seek help.

Copyright ©2017 Catholic News Service / U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops.