We value your privacy

We use cookies to enhance your browsing experience, serve personalised ads or content, and analyse our traffic. By clicking "Accept All", you consent to our use of cookies.

We use cookies to help you navigate efficiently and perform certain functions. You will find detailed information about all cookies under each consent category below.

The cookies that are categorised as "Necessary" are stored on your browser as they are essential for enabling the basic functionalities of the site. ...

Necessary cookies are required to enable the basic features of this site, such as providing secure log-in or adjusting your consent preferences. These cookies do not store any personally identifiable data.

No cookies to display.

Functional cookies help perform certain functionalities like sharing the content of the website on social media platforms, collecting feedback, and other third-party features.

No cookies to display.

Analytical cookies are used to understand how visitors interact with the website. These cookies help provide information on metrics such as the number of visitors, bounce rate, traffic source, etc.

No cookies to display.

Performance cookies are used to understand and analyse the key performance indexes of the website which helps in delivering a better user experience for the visitors.

No cookies to display.

Advertisement cookies are used to provide visitors with customised advertisements based on the pages you visited previously and to analyse the effectiveness of the ad campaigns.

No cookies to display.

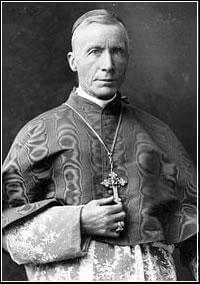

Ninth Archbishop of Baltimore

Ninth Archbishop of Baltimore

Motto: Emitte Spiritum Tuum. “Send forth thy Spirit.” (Psalm 103:30)

James Gibbons was born in Baltimore on July 23, 1834, the son of Thomas Gibbons, a clerk, and Bridget Walsh Gibbons. He was baptized in the cathedral from which he would be buried.

Gibbons’ parents had come to the United States about 1829 but returned to Ireland in 1837. There his father ran a grocery in Ballinrobe, County Mayo, until his death in 1847. The widow and children returned to the United States in 1853, establishing their residence in New Orleans. There James worked in a grocery store until inspired by a Redemptorist retreat to become a priest. In 1855 he entered St. Charles College, the minor seminary in Baltimore, and in 1857 St. Mary’s, the major seminary. On June 30, 1861, he was ordained by Archbishop Francis Patrick Kenrick of Baltimore, who had accepted him for his archdiocese. For six weeks Gibbons was assistant at St. Patrick’s parish, then appointed first pastor of St. Bridget’s, originally a mission of St. Patrick’s. There he served as a chaplain for Fort McHenry during the Civil War.

In 1865 Archbishop Martin John Spalding summoned Gibbons to be his secretary and help prepare for the Second Plenary Council of Baltimore. At the council the assembled fathers, at Spalding’s prompting, recommended Gibbons for the vicariate apostolic of North Carolina, whose creation they also recommended. Named titular bishop of Adramyttium on March 3, 1868, Gibbons was raised to the episcopacy by Spalding on August 15, 1868, the youngest of more than a thousand bishops in the Catholic world.

The vicariate, the entire state of North Carolina, had fewer than seven hundred Catholics. Gibbons made a number of converts, but finding the apologetical works available inadequate for their needs, he determined to write his on; Faith of our Fathers would prove the most popular apologetical work written by an American Catholic. At Vatican Council I, where he was also the youngest bishop, he voted in favor of papal infallibility. In January 1872 Gibbons was named administrator of the Diocese of Richmond, one of Archbishop Spalding’s last requests, and on July 30, bishop of Richmond, retaining his charge of North Carolina. In Richmond his principal task was providing teachers for his schools. At the wish of Archbishop James Roosevelt Bayley of Baltimore, he was named his coadjutor with right of succession on May 25, 1877. Upon Bayley’s death on October 3, 1877, Gibbons became archbishop of the premier see.

In his first ten years as archbishop, Gibbons had neither large plans nor great ambitions. He believed his archdiocese well endowed in personnel and institutions, which, in fact, it was. Though he did not instigate, he put no brakes on the proliferation of parish societies that occurred throughout his administration, the knighthoods and young men’s literary societies, especially in his first decade. The greatest problems with which he had to contend were those that arose from the influx of new immigrants: the Bohemians, Poles, Lithuanians, and Italians. Though his approach to most difficulties was a “masterly inactivity,” he had on more than one occasion to intervene in the affairs of their troublesome parishes but was unable at one to prevent a Polish schism.

In 1884 the archbishop of Baltimore was chosen by the pope to preside over the Third Plenary Council of Baltimore, a gathering for which Gibbons initially showed little enthusiasm. The council, however, produced the most comprehensive body of legislation for the Catholic Church in America. On June 7, 1886, Gibbons was made a cardinal, the second American so honored. On March 17, 1887, he received the red hat in Rome, and a week later at his titular church, Santa Maria in Trastevere, delivered a stirring sermon in praise of his native land and its political principles.

In Rome Gibbons formed a close bond with three other Americans in their efforts to resolve a number of problems: Bishop (soon Archbishop) John Ireland of St. Paul; John Keane, rector designate for The Catholic University to be established in Washington, D.C.; and Denis O’Connell, rector of the North American College in Rome. Together they won Roman approval for The Catholic University despite the opposition of Archbishop Michael Corrigan of New York and the Jesuits. The four prevented a Roman condemnation of the Knights of Labor and the public condemnation of the works of Henry George demanded by Archbishop Corrigan. One of Corrigan’s priests, Edward McGlynn, had, despite Corrigan’s prohibition, espoused the cause of George, whom Corrigan considered socialistic. The four also successfully countered a petition of German Catholics in the United States for a greater degree of autonomy that was highly critical of Irish bishops. The defense of the Knights of Labor was signed by Gibbons alone and won for him a reputation as champion of the working class.

Gibbons, Ireland, Keane and O’Connell came to be recognized as the leaders of the “liberals” in the Catholic hierarchy; Corrigan and Bishop Bernard McQuaid of Rochester as spokesmen for the conservatives, who also included most of the German bishops. When German discontent surfaced again in what was called the “Cahensly affair,” Gibbons delivered in 1891 a forceful sermon in the cathedral of Milwaukee denouncing those who would “sow tares of discord in the fair fields of the Church in America.”

Though hitherto supportive of parochial schools, Gibbons rose to the defense of Archbishop Ireland in 1891 and his Faribault plan that would incorporate parish schools into the public school system, a measure strenuously opposed by Corrigan, McQuaid, the Germans, and the Jesuits. Rome declared that the plan could be tolerated, but in 1893 sent a permanent apostolic delegate to the United States, Francesco Satolli, to resolve this and other points of conflict. Satolli’s initial sympathy for the liberals was indicated not only by his support of the Faribault plan but also by his lifting of the excommunication of Edward McGlynn imposed by Archbishop Corrigan. Uneasy, however, with the participation of Gibbons and Keane in the World’s Parliament of Religions in 1893 and Gibbons’ failure to enforce the Roman condemnation of certain secret societies in the United States in 1894, Satolli in 1895 shifted his support to the conservatives, especially in his approval of parish schools and the work of the Germans. The triumph of the conservatives was made obvious by the dismissal of O’Connell as rector of the North American College in 1895 and of Keane as rector of The Catholic University in 1896.

Despite this setback, Ireland, Keane, and O’Connell, with Gibbons’ backing, promoted an agenda for the Americanization of the Catholic Church at home and abroad, especially the acceptance of such principles as the separation of Church and state and the adoption of democratic procedures. Alarmed, European conservatives, particularly in France, seized upon a biography of the founder of the American Paulists, Isaac Hecker, for which Ireland had written a glowing introduction, to have such American Aberrations condemned by the Holy See. In the papal letter, Testem benevolentiae (January 22, 1899) addressed to Gibbons, the heresy of “Americanism” was condemned, actually a medley of beliefs such as a reliance on the Holy Spirit rather than on external guidance, a promotion of the active over the passive or supernatural virtues, and a depreciation of religious vows.

Despite this fatal blow to the Americanizers as a whole, Gibbons continued to play the role of spokesman of the Catholic Church in America splendidly. His public utterances commanded increasing attention. His presence at important national events, usually to deliver the invocation, was given even greater coverage in the press. Gibbons developed a warm friendship with several presidents, especially Theodore Roosevelt. For the celebration of the fiftieth anniversary of his ordination to the priesthood in 1911, business in the national capital came practically to a halt so that almost every politician of note could go to Baltimore to pay their respects.

A part of Gibbons’ popularity derived from the works he authored. Faith of Our Fathers (1876) was published many times over. Also widely read were Our Christian Heritage (1889), Ambassador of Christ (1896), Discourse and Sermons (1908), and A Retrospect of Fifty Years (1916). He contributed a number of essays to such much-read journals as the North American Review and Putnams’ Monthly. His style was simple but compelling. Protestant Americans looked most often to Gibbons for an explanation of the Catholic position on contentious issues.

Gibbons’ views were not always consistent. At the time of the Spanish-American War he was a pacifist, denouncing militarism and the arms race as unchristian. At the outset of World War I he was a strong proponent of preparedness, and during its course urged Catholic men to go forth and be proud of their wounds. Initially an opponent of American imperialism, under the influence of Presidents Roosevelt and Taft he urged the American bishops to oppose the Jones Act designed to dismantle the American Empire. At the local level Gibbons supported such progressive measures as city planning, public health, consumer protection, and the regulation of sweatshops. At the national level he opposed the Seventeenth, Eighteenth and Nineteenth Amendments. The list of his denunciations of the movement for women’s suffrage was embarrassingly long.

Until the day he died Gibbons exercised considerable power in the American Church. As ranking prelate he presided over the annual meetings of the archbishops that began in 1890. He also presided over the transformation of the National Catholic War Council into the National Catholic Welfare Council in 1919. After his reception of the red hat, he came to enjoy the power he seemed to win effortlessly. In 1914 he raised strong objections to the rumors that the national capital would be detached from his archdiocese. He refused to have a coadjutor. He also enjoyed remarkable health until a few days before his death on March 24, 1921, at the age of eighty-seven years and eight months.

More than any other Catholic, not excepting John Carroll, James Gibbons was embraced by his country. He was personable, outgoing, and seldom without a smile. Concern for his reputation, according to some, made him conciliatory but overtly cautious. To a querulous few he was vain, devious, and timid. To most, however, he was assured, prudent, and gentle. With soothing words and disarming rhetoric he was able to retain the affection and esteem of those whose expectations he disappointed most. Quietly he worked to defuse the lay Catholic Congress movement while praising the layman’s efforts. Though in print he continued to champion the cause of the working class, in practice his dealings with labor unions left much to be desired. While he fought a bill to disfranchise Maryland blacks, at a Catholic African American Congress he counseled “wisdom, forbearance, prudence, and discretion.” While he complimented women for their virtue, industry, and piety, he made no effort to hide his disdain for feminists.

As the archdiocese he governed grew in prestige, it declined in proportion to the numerical and institutional indices that marked the growth of other archdioceses. Gibbons was not an institution builder because he was not a wall builder. He desired his immigrant charges to move into the mainstream as rapidly as possible. In this and in other ways he resembled the first archbishop of Baltimore. Like John Carroll, Gibbons evidenced a broad ecumenism in his association with the leaders of other denominations. In his involvement in civic affairs he also resembled Carroll. Like Carroll he was tireless in his praise of American virtues, institutions, and principles. And like Carroll he could interpret Roman directives broadly or ignore them altogether.

The Archdiocese of Baltimore, the apostolic delegate Giovanni Bonzano would report two months after Gibbons’ death, was not in a flourishing condition. Gibbons had shunned acts of administration that involved responsibility or odium and had paid little attention to the decrees of the council over which he had presided. No future American bishop, Bonzano advised, must be allowed to wield the power Gibbons had.

Yet the apostolic delegate was prepared to admit that Gibbons had served the Church well in assuaging intolerance and bigotry. With consummate tact he had become the friend of people of every condition, race, and faith, so that at his death he was exalted as a patriot, a citizen, and a statesman, a man of great vision whose words on national questions were always peaceful and just. Five years before his death the Baltimore Sun had said the same. “The Catholic Church has given many distinguished prelates and priests to its work in this country, but none who has inspired the same general confidence and the same earnest esteem.” Its explanation: “To all he seems to speak in their own tongues by some Pentecostal power, or by some subtle affinity that makes nothing human foreign to him.”

Bibliography

Ellis, John Tracy. The Life of James Cardinal Gibbons, Archbishop of Baltimore, 1834-1921. 2 vols. Milwaukee: Bruce Publishing Co., 1952.

Fogarty, Gerald P., S.J., ed. Patterns of Episcopal Leadership. New York: Macmillan, 1989.

Spalding, Thomas W. The Premier See: A History of the Archdiocese of Baltimore, 1789-1989. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1989.

Will, Allen Sinclair. Life of Cardinal Gibbons, Archbishop of Baltimore. 2 vols. New York: E.P. Dutton, 1922.

By Thomas W. Spalding, CFX

Originally published in Michael Glazier and Thomas J. Shelley, eds. The Encyclopedia of American Catholic History (Collegeville, MN: The Liturgical Press, 1997). Used with permission of author’s estate.