By Brian Welter

Catholic News Service

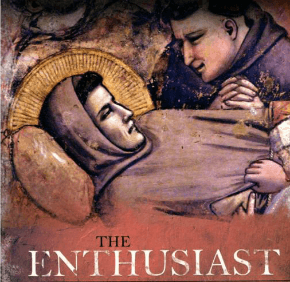

“The Enthusiast: How the Best Friend of Francis of Assisi Almost Destroyed What He Started” by Jon M. Sweeney. Ave Maria Press (Notre Dame, Indiana, 2016). 291 pp., $18.95.

St. Francis of Assisi had a few rough edges, according to Jon Sweeney, who rejects the common practice of making him too saintly.

First, the strong, public and repeated disobedience to his father, so frequently romanticized by the saint’s admirers, amounts to a “flaunting disregard for the fourth commandment,” according to Sweeney. Readers might see parallels here with Martin Luther’s paternal conflict, a relationship much maligned by Catholics over the centuries.

Second, the author succeeds in showing the importance of friendship to St. Francis’ spirituality. These relationships were not always so easygoing. This is an important slant to the story, as usually Francis’ biographers present a docetic individual who is phantom-like in his holy detachment from worldly things yet mystically in unity with the birds and flowers. The author treads into the rocky relationship between the saint and Elias of Cortona, though most of the book sticks to Francis.

Third, Sweeney’s less-than-romantic portrayal of St. Francis’ leadership describes a maturation process which sounds uncomfortably normal.

“It was inevitable that, once Francis had gathered like-minded men around him, he took on a certain air of authority,” he writes. “Even before his efforts were formalized into anything recognized by the church, Francis acquired a reputation as a man not to be easily contradicted. One reason for this is that authority used to attach itself naturally to men who were perceived to be in communication with God. But how surprising this transformation was in Francis: he went from village fool to instructor of bishops and priests in less than two years.”

“The Enthusiast” does contain many traditional views. The author notes the difference between St. Francis as saint and Peter Waldo as heretic despite many close parallels between the two leaders and their movements. The former went out of his way to acknowledge church authority and teaching, and expressly countered the urge toward heresy in his own movement.

Sweeney ties in some of the saint’s more eccentric behaviors with this orthodoxy: “Above all, Francis’ close identification with the created world was his way of combatting with life and practice the most prevalent heresy of the day: dualism.”

The saint’s ideas, with precursors in certain French hermits, for instance, overturned the often lavish spiritual and ecclesiastical ways of the era: Franciscan “simplicity, clarity and precision about the meaning and purpose of a Christian life caught the sophisticated completely off guard. … Until they heard Francis’ Gospel message, they had thought religion to be simply the meeting of obligations, which were minimal and without any real comfort or impact upon one’s life.”

Sweeney uses historical asides, such as regarding the Cathars and Albigensian Crusade, to situate St. Francis in his society. The Cathars are not portrayed in overly abstract, saintly ways, but more truthfully, which again goes against the common practice of depicting these heretics as saintly victims of the terribly patriarchal Catholic Church.

“Their teachings were always insidious and disruptive,” Sweeney writes. “Central to their theology was the way in which they belittled the Godhead” with their “theological and existential dualism extended logically to the second person of the Trinity.”

Sweeney the realist shows how Elias of Cortona, one of St. Francis’ closest lifelong friends and a friar from the early days, took the order in the worldly direction so alien to the founder. The author’s imagery gives readers a strong sense of the depth and suddenness of the Franciscans’ fall under Elias: “Tributes and gifts, whether fancy foods, gold or ornaments for the basilica in Assisi, were always arriving at Elias’ office as indulgences. Fine foods, imported from all over the world, were added to his table. Cherries, crabs, eel, almond milk and cinnamon became common.”

The book answers some of the basic questions regarding the infighting that took place between the “spirituals” and Brother Elias’ more worldly followers who turned the order into an institution not so different from other orders, and how that split had begun well before the death of the order’s founder. This hints at certain failings of St. Francis in ensuring a more peaceful and structured succession.

Overall, then, “The Enthusiast” offers a refreshing departure from the more naive renditions of St. Francis and the early Franciscans.

Read more movie and book reviews here.

Read more movie and book reviews here.

Copyright ©2016 Catholic News Service/U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops.