By Erik Zygmont

ezygmont@CatholicReview.org

Twitter: @ReviewErik

ANNAPOLIS – You stop eating six hours before you want to die. With one hour to go, you ingest a pill that enhances the body’s absorption faculties, and you take something to keep yourself from throwing up. Finally, you stir a lethal powder into water – or something sweet, to offset the bitter taste – and drink it all within two minutes. You fall asleep in about five minutes. You never wake up.

At the request of Del. Deborah Rey, the culmination of the physician-assisted suicide process was described by Kim Callinan, chief program officer of Compassion and Choices, the national organization pushing for its widespread legalization.

The first major public debate on the topic in the 2016 Legislative Session brought eight hours of testimony to a Feb. 19 joint hearing with the House of Delegates Judiciary Committee and Health and Government Operations Committee.

Doctors, psychiatrists, religious leaders and everyday people familiar with suffering and death spoke strongly on both sides of the issue and agreed on very little, including what words should be used to describe it.

“Our antennae should always go up when people start using euphemisms,” commented Dr. Kevin Donovan, director of the Georgetown University Center for Clinical Bioethics.

Proponents of physician-assisted suicide prefer to call it aid-in-dying and say that there is no suicide involved. The bill itself, last year dubbed the Death with Dignity Act, has become the End-of-Life Option Act.

Per the bill, terminal patients whose doctors give them prognoses of death within six months would be eligible to obtain prescriptions for lethal drugs, which they would then consume via the process outlined above.

Opponents attacked the bill on numerous grounds. While many proponents characterized the measure as a liberation from suffering, several opponents noted that surveyed patients in Oregon have cited the loss of autonomy as their major reason for choosing to die, with pain and suffering lower down on the list.

Several opponents took issue with the fact that the underlying disease would be listed on the death certificate as the cause of death, not the deceased’s ingestion of lethal drugs.

“I just want to make sure that you all understand that we physicians are taught to put the proximate cause of death (on a death certificate), said Dr. Steven Levenson, a post-acute care specialist who was involved in the 1993 passage of the state’s Healthcare Decisions Act. “It’s kind of disingenuous to say, ‘Don’t worry about it, we’re just going to put ‘natural causes,’ ” he said.

Several proponents stated that the lack of the assisted-suicide option had robbed their loved ones of dignity as they died. Opponents of the bill told different stories.

Carroll County resident Beth Puleo, a 2013 graduate of Mount St. Mary’s University in Emmitsburg, recounted the struggles of her family.

When she was a toddler, her father was diagnosed with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS). Doctors gave him two years to live, but he would go on to live eight.

Two years after his diagnosis, Puleo, then 5, was diagnosed with brain cancer. After two surgeries, the tumor grew back.

Radiation was the only option, Puleo said, and her family went ahead with it. After a summer of treatment, her cancer was destroyed, but the radiation left her severely disabled, unable to “walk, crawl or do much of anything.”

Doctors, Puleo said, told her parents to “take her home, love her, and she’ll be dead in a couple weeks.”

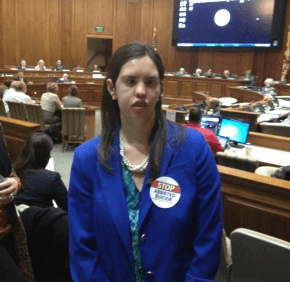

“Here I am, almost 20 years later, a college graduate,” she said.

Her father’s prolonged battle with ALS was, she said, a critical component of his life as well as her recovery.

“If my dad had chosen death, he never would have seen his daughter fight cancer and win,” Puleo said.

At the same time, she added, her father’s fight impacted her.

“His struggle – seeing him fight to the end – inspired me to work harder,” she said.

Puleo, who remains disabled, did not imply a fairy-tale ending to her story.

“There are some days I hate being disabled,” she said, though she added that she lives by two maxims: “Every day is a new beginning, and what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger.”

Testifying against the bill on behalf of the Arc Maryland, an advocacy organization for those with intellectual and developmental disabilities was Poetri Deal, its director of public policy and advocacy.

“The Arc believes there is a clear danger that individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities who are suffering will not be advised of other options,” she said. “Historically, their lives have been devalued as compared to those without disabilities,” she added, noting that that population has already been subject to cruelties such as involuntary sterilization and shock treatment, “all in the name of the ambiguous phrase ‘quality of life.’ ”

Several opponents of the bill expressed concern that legalized assisted suicide would increase suicide across the board, citing a study published in 2015 in the Southern Medical Journal. The abstract states that legalizing assisted suicide is associated with a 6.3-percent increase in suicides overall, and no decrease in non-assisted suicides.

“This suggests that (physician-assisted suicide) either does not inhibit … non-assisted suicide, or that it acts in this way in some individuals but is associated with an increased inclination to suicide in other individuals,” the abstract states.

Ron Pilling, a board member of the Jesse Klump Memorial Fund, a scholarship fund dedicated to a teenaged suicide victim in Snow Hill, called the legalization of assisted suicide “a green light,” an incentive for a suicide that might otherwise be avoided.

It was clarified over the course of the hearing that the patients unable to administer the medication themselves – those paralyzed from the neck down, for example – would be barred from choosing to end their lives. Opponents of the bill argued that if passed, the law would likely be judged as discriminatory, and the option to be killed would have to be extended to those who would need somebody else to perform the action.

“I think it’s a door that, once it’s opened, it can’t be closed,” testified Mary Ellen Russell, executive director of the Maryland Catholic Conference, the legislative lobbying arm of the Maryland bishops, which opposes the bill.

“The logic of saying that this is only going to apply to a certain group of people who have a terminal illness and are suffering, when there are all kinds of people who are suffering, doesn’t make sense,” she said.

Russell also asserted that the bill should not be framed in the question of whether an individual has the right to die.

“The question here is whether we want to involve the medical community – a doctor – facilitating this and helping someone make this choice,” she said.

She and others suggested that the state would better expend its energies in expanding palliative care.

The End-of-Life Option Act is scheduled to be heard in the State Senate Feb. 25.

Also see:

Bigger fight against assisted suicide in Maryland expected in 2016

Catholics converge on Annapolis: Opposing assisted suicide big draw for some