By Patricia Zapor

Catholic News Service

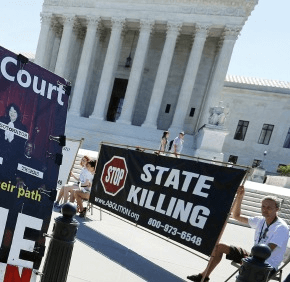

WASHINGTON – In another in a series of bitterly divided end-of-term cases, the Supreme Court June 29 upheld the execution protocol used by Oklahoma and several other states.

The 5-4 ruling written by Justice Samuel Alito upheld lower courts that said the use of the drug midazolam in lethal injection does not violate Eighth Amendment protections against cruel and unusual punishment.

The ruling was among the last three opinions released, closing out the court’s 2014 term. Aside from announcing the disposition of other cases it has been asked to review, the court is not scheduled to conduct any further business in the public eye until the 2015 term opens Oct. 5.

The majority opinion in Glossip v. Gross noted that it has been previously established multiple times that capital punishment is constitutional and only delved into whether the claims by Oklahoma death-row inmates that the effects of the drugs used in lethal injection are unnecessarily painful. Among the reasons Alito cited in upholding lower courts were that “the prisoners failed to identify a known and available alternative method of execution that entails a lesser risk of pain.”

Justices Antonin Scalia and Clarence Thomas each filed concurring opinions. Alito’s majority ruling also was joined by Chief Justice John Roberts, Scalia, Thomas and Justice Anthony Kennedy.

Two of the four justices who disagreed with Alito each wrote a dissenting opinion, including one in which Justices Stephen Breyer and Ruth Bader Ginsburg called for briefings on whether the death penalty itself ought to be ruled unconstitutional. “I believe it highly likely that the death penalty violates the Eighth Amendment,” Breyer wrote. “At the very least, the court should call for full briefing on the basic question.”

In his majority ruling, Alito discussed at length the evidence presented about whether midazolam fails to act sufficiently as a sedative to prevent inmates who are being executed from suffering an undue amount of pain. The cases arose after several situations like that of Clayton Lockett. At his April 2014 execution, he writhed in pain for 40 minutes before dying of apparent heart failure.

Alito recounted the circumstances leading to the use of midazolam, which has become an alternative for other drugs, whose manufacturers refuse to supply them for use in executions. He went into graphic detail about the murders committed by the death-row inmates who sued.

In his concurrence and pointed disagreement with Breyer, Thomas also described brutal crimes that landed people on death row. It was the third criminal justice case in the last weeks of the term in which Thomas has made a point of writing about severe sentences being necessary because of the pain inflicted on crime victims and their families.

Like Alito’s majority opinion, Sotomayor devoted much of her dissent to dissecting the testimony about the effects of midazolam. She took issue with the majority brushing past the inmates’ plea “that they at least be allowed a stay of execution while they seek to prove midazolam’s inadequacy.” She was joined in the dissent by Breyer, Ginsburg and Justice Elena Kagan.

Sotomayor said the court accomplished that “first, by deferring to the District Court’s decision to credit the scientifically unsupported and implausible testimony of a single expert witness; and second, by faulting petitioners for failing to satisfy the wholly novel requirement of proving the availability of an alternative means for their own executions. On both counts the court errs. As a result, it leaves petitioners exposed to what may well be the chemical equivalent of being burned at the stake.”

She said that in sweeping aside substantial evidence that midazolam “cannot be utilized to maintain unconsciousness in the face of agonizing stimuli,” the majority accepted one witness’s “wholly unsupported claims that 500 milligrams of midazolam will ‘paralyze the brain.’ In so holding, the court disregards an objectively intolerable risk of severe pain.”

The majority responded to Sotomayor’s points about the potential for such an outcome by calling it a “groundless suggestion that our decision is tantamount to allowing prisoners to be ‘drawn and quartered, slowly tortured to death, or actually burned at the stake.’ That is simply not true and the principal dissent’s resort to this outlandish rhetoric reveals the weakness of its legal arguments.”

Scalia’s concurring opinion — joined by Thomas — mostly took on Breyer’s dissent, faulting him for suggesting the death penalty might be unconstitutional.

“Mind you, not once in the history of the American Republic has this court ever suggested the death penalty is categorically impermissible,” Scalia wrote. “The reason is obvious: It is impossible to hold unconstitutional that which the Constitution explicitly contemplates. The Fifth Amendment provides that “[n]o person shall be held to answer for a capital … crime unless on a presentment or indictment of a grand jury,’ and that no person shall be ‘deprived of life … without due process of law.’ Nevertheless, today Justice Breyer takes on the role of the abolitionists in this long-running drama, arguing that the text of the Constitution and two centuries of history must yield to his ’20 years of experience on this court,’ and inviting full briefing on the continued permissibility of capital punishment.”

Breyer’s argument, Scalia wrote, “is full of internal contradictions and (it must be said) gobbledygook.”

Also see:

After decades of Catholic activism, death penalty repeal becomes law in Maryland

Copyright (c) 2015 Catholic News Service/U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops