By Erik Zygmont

ezygmont@CatholicReview.org

Twitter: @ReviewErik

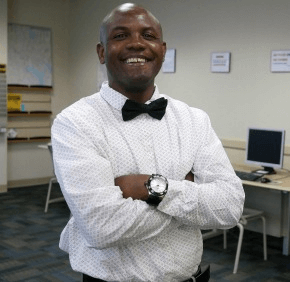

Thirty-nine-year-old Randy Johnson sees himself as a “success story in development,” though that status was less than evident two decades ago.

Growing up in West Baltimore, he dropped out of high school in 1994 because “I thought the streets would cater to my life.”

Selling drugs led to a period of incarceration, low-wage jobs upon release, alcoholism, unpaid bills and, eventually, homelessness. He couldn’t deny that something was wrong.

“I always had intelligence,” Johnson said. “I always felt like I wanted to do more, but this was the life for me.”

In the summer of 2014, he realized it wasn’t.

“I decided to give Christopher Place a try,” he said.

Christopher Place Employment Academy is an educational program for formerly homeless men located at the Catholic Charities of Baltimore complex at 725 Fallsway.

Christopher Place Employment Academy is an educational program for formerly homeless men located at the Catholic Charities of Baltimore complex at 725 Fallsway.

Men commit a minimum of six months to a residency program in order to “acquire the necessary skills and financial standing to be successful in the community,” according to an overview of the program on the Catholic Charities website, catholiccharities-md.org.

The men then use what they’ve learned to search for jobs while continuing to take classes and perform community service. Once a job is obtained, the participant continues to receive support and “financial responsibility is emphasized and long-term career and housing plans are developed.”

Finally, the men transition into stable housing and independence.

Johnson, about halfway through the program, has become an example. On recent classroom tours, new enrollees sought him out in the hallway to shake his hand.

Part of his journey through Christopher Place has been the uncovering and developing of innate abilities and talents that he will eventually contribute to the workforce and society as a whole.

Gifted with exceptional written and oral communication skills, Johnson has been enlisted to speak on social-justice-oriented topics – such as the relationship between past criminal offenses and future employment – in Annapolis. While he was in prison, he said he wrote several novels, which he acknowledges are semi-autobiographical and deal with “what I see every day in urban communities.”

“My character is a sensible guy,” Johnson said. “He’s done the same things I’ve done, and he’s recognized it’s not working.”

Recognizing what does work, Johnson added, requires a measure of faith and perseverance.

“The transition from the streets to in here – I don’t want to say it was smooth,” he said. “I had to get it into myself that I had to do things differently.”

With pithy phrases like “Take the cotton out of your ears and put it in your mouth,” instructors helped drive the message home, he added.

Johnson “capstoned” – Christopher Place jargon for completing the intensive classroom portion of the program – in February. He now works for the Weinberg Resource and Housing Center, an emergency shelter under the Catholic Charities umbrella that provides homeless services to 275 adults.

He is looking toward a career in HVAC, and like a large percentage of Christopher Place alumni, plans to stay connected to the program after he graduates.

“I would love to come back to Catholic Charities five years from now and talk to people about my life,” he said.

Such a conversation would likely touch on the death of Freddie Gray Jr. and the unrest that followed.

“Freddie Gray is me,” Johnson said. “I’ve been through the same scenarios of police brutality.”

He suspects that the style of dress he has adopted – he wore a bowtie and loafers to his interview with The Catholic Review – accounts for the fact that it hasn’t happened recently.

Johnson added that he does not agree with violence and arson as a form of protest, but does pose a question: “If that didn’t happen, would we still have the same result – those officers being charged?”

For himself, an inner voice keeps him focused and out of the fray.

“No, Randy. You’ve got something you have to do in life.”

Also see:

Pope offers ‘Stone Age’ tips to youth for living the digital world well

‘Victory’ app aimed at helping young people suffering addiction to porn