By George P. Matysek Jr.

gmatysek@CatholicReview.org

The mysterious voice on the other end of the phone was grave and insistent.

“Get out of there – right now,” the anonymous caller told Antonio Arredondo as the accountant was finishing up a day’s work in the Cuban Treasury Department more than 50 years ago.

“Trust me,” the caller said. “The militia is coming to get you. Leave.”

Arredondo escaped out a window. Using a tourist visa, he fled to the United States where his friend, Baltimore Orioles’ shortstop Willie Miranda, ultimately found him a job washing trailers at a transportation company in Baltimore.

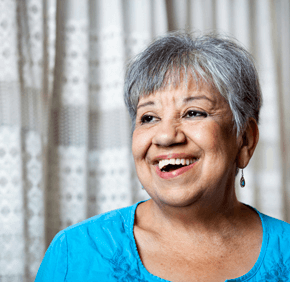

Estella Chavez, Arredondo’s daughter and a 73-year-old parishioner of Sacred Heart of Jesus-Sagrado Corazón de Jesús in Highlandtown, remembers facing immediate Communist retaliation as a student in Havana.

“The day after my dad left, the militia came with rifles asking for him,” she said. “I said I didn’t know, and they took a television set that was in my room.”

Because her father was branded a traitor, Chavez was ordered to withdraw from the law program at the University of Havana, where she was a student. The day she was given the news, the then-18-year-old member of Catholic Action was mocked for her Catholic faith.

“They asked me how I could believe in something you’ve never seen,” Chavez recalled. “They called us anti-social.”

The experience of having her faith, life and freedom threatened only strengthened Chavez’s hold on her beliefs. After following her father to the United States, Chavez raised a family and devoted much of her life to serving the church she loves.

For more than a decade, Chavez worked directly with leaders of the Archdiocese of Baltimore – serving as a secretary to Cardinal William H. Keeler, Cardinal Edwin F. O’Brien and Archbishop William E. Lori. After retiring in December, she went back to what she calls the “trenches,” ministering in children’s religious education at her parish.

Throughout, Chavez said, she has been inspired by priests, bishops and lay people who make sacrifices for the faith.

“Faith ties it all together,” Chavez explained, sitting in a modest adoration chapel at Sacred Heart. “I’ve seen the church at the high end and I’ve seen it in the trenches. It’s all amazing.”

As one of several secretaries to the archbishop, Chavez distributed mail, took care of processing papal blessings, translated homilies into Spanish and performed other duties. She was often the first voice of the church people heard when they called the archbishop’s office.

“During the sex abuse scandals, it was very hard,” she said. “People were upset and we were there to help them with that.”

Chavez remembered one call from an elderly woman dying of cancer who was distraught after a media report about a controversy in the church. She kept asking what was happening to her faith.

“We were able to reassure her that nothing is happening to the faith as it always was,” said Chavez, who also assisted retired Archbishop William D. Borders and served as a secretary, for one year in the archdiocesan Hispanic ministry office and five years in the Division of Catholic Schools.

A mother of two and grandmother of four, Chavez called it a blessing to serve the church. Prayers for her native Cuba and for religious freedom everywhere are always in her heart.

“What was good for me is that I was able to work in a place where I was able to be a Catholic,” she said. “Being Catholic is the central thing in my life.”

Also see: