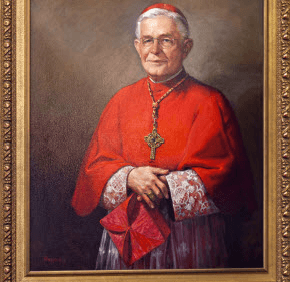

By The Most Rev. Lawrence J. Shehan, D.D.

Archbishop of Baltimore

March 1, 1963

Dearly Beloved in Christ,

IN THE MONTH OF NOVEMBER 1958, the Bishops of this country at their annual meeting issued a statement entitled “Discrimination and the Christian Conscience.” After noting the rather remarkable progress made by our Negro fellow citizens, particularly during and after the Second World War, toward such goals as political equality, fair educational and economic opportunities, good housing without exploitation, and a full chance for social advancement, the Bishops went on to say that in more recent years “the issues have become confused, and the march toward justice and equality has been slowed, if not halted, in some areas. The transcendent moral issues have become obscured and possibly forgotten.”

“The heart of the race question,” they declared, “is moral and religious. It concerns the rights of man and our attitude toward our fellow man. If our attitude is governed by the great Christian law of love of neighbor and respect for his rights, then we can work out harmoniously the techniques for making legal, educational, economic, and social adjustments. But if our hearts are poisoned by hatred, or even by indifference toward the welfare and rights of our fellow man, then our nation faces a grave internal crisis.”

Among the signers of that document was my beloved predecessor, Archbishop Keough, who was then serving as Chairman of the Administrative Board of the National Catholic Welfare Conference. That the statement served as an expression of his personal conviction on the subject of racial discrimination, no one who knew him could doubt. Coming from a part of the country where such discrimination had never been a major issue, he at first found it difficult to realize the urgency of the problem here, in a State which lies midway between North and South, whose northern boundary has long symbolized the social barrier between two so diverse sections of this country. His gentle and charitable mind found it particularly hard to believe that some of his people would not be convinced and guided by the statement of principle issued by the Bishops of this country as their official teaching on the subject of race relations.

MOREOVER, THE ILLNESS which weighed so heavily upon the Archbishop during the latter years of his tenure prevented him from coming to closer grips with the baffling racial problem and from issuing public directives on this subject to his priests and people. Events, however, which have occurred during the past 18 months, have brought to me the conviction that I ought at this time to speak out in reverence for his memory and in fulfillment of my own duty of conscience.

A pastoral letter on this subject, moreover, seems particularly appropriate in this year when we are observing the centenary of the Proclamation of Emancipation issued by President Lincoln on January 1, 1863. With that document, this country formally undertook to correct and undo the moral and social evil of slavery which had afflicted it from the beginning. The breaking of the shackles of bondage, however, was only the beginning of the process to which this country stood committed. The document by which our forefathers declared their political independence clearly stated the principle by which they justified their rebellion and guided their action in forming a new government: that all men are created equal and are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, among which are life liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

The struggle to give adequate expression to this principle has been long and arduous. There has been, however, real progress during the past century and – as noted by the American Bishops – particularly during the last generation. Yet it is no exaggeration to say that in hardly any State of the Union has complete social, political, economic, and educational equality been established. In some states, the barest beginnings have only recently been made, under intense Federal pressure. Here in our own State, recent experience has shown that much – very much – remains to be none; that grave wrongs still need to be righted.

NOTHING SHOULD BE more evident to the fair-minded citizen than the fact that the equaled proclaimed by our Declaration of Independence, and the freedom described by it as “unalienable” requires, as a very minimum of justice, the right to equal accommodations, both on public property and within those enterprises licensed and protected by the State for the service of the general public. Yet our proposed State law of equal accommodations has thus far been emasculated by our State legislators. In. our own See city, although there is glaring public evidence of the failure to recognize the right of equal accommodation as properly belonging to the Negro, we are – for the present at least – without such an ordinance.

In this, the oldest and most venerable See in the United States, it should be particularly disconcerting to all of us to know that last year an equal accommodations ordinance then before the Baltimore City Council failed to receive the support of some Catholic legislators who represented districts heavily Catholic in population. Does this mean that many of our own people have failed to recognize the serious duty of justice which flows from the basic equality of men of all races and all social conditions?

Such a failure is all the more regrettable since our Christian faith imposes upon us all a special duty of both justice and charity toward all men, no matter what may be their racial and social origin. By the very terms of Christian teaching, we believe that all men are God’s special creatures, made to His image and likeness. We believe that the Son of God, Jesus Christ, the God-man, came into the world to save all men; that on the Cross of Calvary He shed His Blood to redeem all of us from our iniquity – all, without any exception. In our Christian eyes then, there is a fundamental bond that links us all together in the sight of God and in the order established by Him. We have an essential duty in justice to recognize and to respect equally the rights of all men.

AS CATHOLICS, WE HAVE an even higher and more sacred duty to all those who are “of the household of the faith.” In his Epistle to the Galatians (3:28), St. Paul tells us: “You are all children of God through faith in Christ Jesus. For all you, who have been baptized into Christ, have put on Christ. There is neither Jew nor Greek; there is neither slave nor freedman” – and today St. Paul would certainly have added: There is neither black nor white; neither brown nor yellow – “for you are all one in Christ. Therefore, you are no longer stranger” and foreigners, but you are citizens with the Saints and members of God’s household. You are built upon the foundation of the Apostles and Prophets with Christ Jesus as the chief cornerstone. In Him, the whole structure is closely fitted together and grows into a temple holy unto God; in Him, too, you are being built together into a dwelling-place for God in the Spirit” (Ephesians 2:19-22).

Nay more, according to the testimony of the same Apostle, by faith and by baptism we have been incorporated into the Mystical Body of Christ. For although Christ has given us different functions within His Church, He has done this “for the building up of the Body of Christ,” which is His Church, of which Christ Himself is the Head; “for from Him the whole body derives its increase to the building up of itself in love” (Ephesians 4 :12).

Within this household of the faith, this temple holy to the Lord, this dwelling place of God in the Spirit, this Mystical Body of Christ, there can be no room for racial discrimination and the bitterness and rancor that inevitably grow out of it. In this year, when the minds and hearts of men are turning longingly and hopefully toward the goal of Christian unity, it is particularly important that justice and charity, without any discrimination or prejudice or antipathy, should shine brightly within the Church of Christ. There is, we know – and there can be only one center of Christian unity: Christ and His Mystical Body. But how can that Body be recognized for what it is unless there is within it unity without division or dissension, and unless within and between its members there shine the justice and charity of Christ?

WITHIN THE TIME and space available to me in this letter, it is impossible to set forth in detail the extent and the nobility of the duty of justice and charity incumbent upon us as members of Christ’s Mystical Body. Under the circumstances of today, however, it may be useful if I attempt to state briefly the minimum that is required of us as members of Christ’s Church in this Archdiocese.

There is, I hope, no need to say that in our churches and in our parochial life generally there must be not only no racial segregation, but also no distinction of rank or place or treatment based upon racial difference: ” … because we are members one of another … Do not grieve the Holy Spirit of God in Whom you were sealed for the day of redemption” (Ephesians 4:25, 30). “For now the justice of God has been made manifest … through faith in Jesus Christ upon all who believe. For there is no distinction: as all have sinned and need the glory of God” (Romans 3:21-23).

In our schools, both elementary and secondary, the same general policy holds. As Catholic schools, they are meant primarily, although not exclusively, for Catholic students – for all Catholic students insofar as facilities can be made available – without racial or any other discrimination. This means that in the registration of students a common policy; approved by our Catholic School Board, must be followed in the case of all Catholic children living within the boundaries of every parish fortunate enough to have its own school. The same policy must govern all transfers from one school to another. Within the school, identical academic standards must apply to all students, and all must be treated with equal justice and charity.

In our diocesan organizations and institutions of charity, a sincere effort has been made over a period of years to eliminate discrimination and to effect true integration. Longstanding social and cultural patterns have at times made this process difficult. With the opening of the new St. Vincent’s Home, we believe that the last traces of discrimination in this field will disappear.

IT IS SOME MONTHS now since-all our Catholic hospitals gave formal approval and acceptance to the policies of non-discrimination I specifically proposed to them. This means that they have agreed to admit and treat applicants for medical and surgical service without distinction in their out-patient departments; to follow the same procedure in admitting patients into the hospital, and in assigning beds to them· that there shall be no discrimination practiced in handling applications for membership on medical, surgical, and nursing staffs; that advancement within each staff will be governed only by ability, training, experience, and character: that a policy of integration and non-discrimination is to be effective for all employees of the hospital.

Some of these policies have been in effect in each of these fields for a long time. We do not claim that they go beyond mere justice. I have spelled them out in some detail because of questions which have been raised from time to time.

The duty of justice and charity applies not only to our churches, our schools, our charitable organizations and institutions, and our hospitals, but also to all of us as individuals. It must guide us in our personal relationships – within our block, our neighborhood, our community; in our social and fraternal organizations; in the business we may conduct; in the labor unions to which we may belong; at work and at play; in all the circumstances of everyday life.

PARTICULARLY LAMENTABLE is the unreasonable and automatic panic, too often fanned by unscrupulous and disreputable real estate brokers and speculators, which accompanies the arrival of a Negro family in an area previously occupied by white families only. The flight that occurs not only unfairly pre-judges the new neighbors, but it also works an economic hardship on departing property owners, destroys the community, undermines church life, and hits hard at substantial investments made in schools, rectories, convents, and recreational facilities, as well as in the actual places of worship.

In order to forestall irrational panic and precipitate flight with all their harmful effects it is important for us to bear in mind what is sought by the average Negro family which, having improved its economic condition, desires to acquire a home in a stable neighborhood of good economic and social standards. The head of such a family is seeking a place where he and his family can live in peace, freedom and dignity; where he and his wife can raise their children in moral and physical safety; where they can give them good education and training; where the whole family can function as good citizens and as useful, respected and valued neighbors. They certainly do not desire to cause the disintegration of the neighborhood or to lower its standards.

On the contrary, they ought to be expected to contribute to the best of their ability to the betterment of the neighborhood, to its stability, to the improvement of its social and economic standards. It is to their advantage to do so. They understand, as do all of us, that with the exercise of every right go corresponding responsibilities. Their neighbors, expecting them to fulfill their responsibilities, ought to help, and not make it more difficult for them to do so. I do not say that there are no individuals who are activated by lower and more selfish motives – just as there are unscrupulous speculators and brokers. But we have at hand a ready, if not always simple and easy, remedy – to refuse to be panicked, to refuse to yield to unscrupulous aggression, to welcome the newcomers into associations dedicated to neighborhood stability and betterment. In the face of such an attitude and policy, were they to become general, the unscrupulous speculator would soon find his speculations unprofitable and the disreputable broker would shortly be driven from business.

Nor can we afford to overlook the crippling effect that division and dissension within our community have on our efforts to meet what is perhaps the most alarming problem of this and every other large city of the country – crime. This is not the place to go into the sources or causes of crime within our midst. Suffice it to say that no part or group of our people has a monopoly on those sources or causes. What should concern us is that the problem is so great as to call for the best minds and the combined intense and persistent efforts of the ablest leaders of all elements within the community. In saying this, we reflect in no way on the police force of either city or state. On the contrary, we have complete confidence in the integrity and ability of both the heads and the ranks of our police departments. But this problem is one that requires the continuing scrutiny and efforts of the community as a whole. It will not be met adequately if there is dissension, division, suspicion, between the two chief racial groups of our citizens.

Even to enumerate our present duties and policies brings vividly to our minds our past defects. Those defects we frankly admit. With humility and regret, we Catholics must acknowledge that we have been all too slow in the correction of our shortcomings, although in the light of the experience of many of our forefathers, we should have been particularly sensitive to the unjust inequalities suffered by other groups. For this reason, we have a special obligation to place ourselves in the forefront of movements to remove the injustices and discriminations which still remain.

WE ARE ALL AWARE OF the present grave social problems which have had their origin in racial prejudices and tensions, and which are fed by long-standing racial antipathies. These problems cannot be suddenly solved or wiped out by wishful thinking or good intentions. They are community problems. They, therefore, cannot be successfully met by any one part of the community nor any one group, however highminded and earnest. They call for the combined thought and planning and co-operation of all of us. They require patience and understanding and good will, and persistent effort on the part of everyone. They call for a sense of justice, above all in that part of the community in which the evil had its origin, and a spirit of charity on both sides.

In their 1958 statement, the Bishops of this country, while calling for concrete plans for the elimination of discrimination and the establishment of equal justice and opportunities, urged that such plans be based upon prudence – the virtue which inclines us to view problems in their proper perspective. The problems we inherit today, they noted, are rooted in decades, even centuries, of custom and cultural patterns. When we are confronted with complex and far-reaching evils, it is not a sign of weakness or timidity to weigh carefully the proposed remedies and reforms. Some changes are more necessary than others. Some may be easy to achieve; others may seem impossible at a given time. It is the mark of wisdom, rather than of weakness, to study problems fully and to form plans carefully. Prudence will indeed guard against the rashness which may endanger solid accomplishment – but prudence must never serve as an excuse for inaction or unnecessary gradualism, or as a reason for not holding a straight, steady course toward our goal of full justice.

IN THIS LETTER, MY dearly beloved people, I have spoken chiefly of our duties of justice, because they are so basic to our relations with our fellowmen. During this season of Lent, it is well for us to ponder these duties and to reflect on our conduct to see whether our attitude and our acts measure up to what God requires of us. Lent, furthermore, is a season of repentance when, having seen clearly our shortcoming, we seek to bring about the needed reforms. But Lent is also a season when the Church places constantly before us the mystery of our Redemption – the mystery of God’s infinite love for us which seeks from us in return not only love for Himself, but also love for our fellowmen. In that magnificent passage from the First Epistle to the Corinthians which formed the lesson of last Sunday’s Mass St. Paul has shown us what our Christian love for each other must be: “Charity is patient, is kind, does not envy, is not pretentious … rejoices with the truth bears all things, hopes all things, endures all things … If I have not charity I am nothing, I have become as sounding brass or a tinkling cymbal.” These words of the Apostle serve as a commentary to our Lord’s saying: “By this shall all men know that you are My disciples, that you have love one for another” (John 13:35).

In this Era of the Second Vatican Council, Pope John has given us an example not only of the charity but also of the wisdom and courage which we here in the Archdiocese of Baltimore need for the solution of the problems of race prejudice and discrimination which we find within our civil community and also within our Catholic community, our own particular “household of the faith.”

It has been due to the wisdom of our present Holy Father and his two great predecessors that the Council presents to the world a true image of the unity and universality of the Church as Christ must have meant it. In the Hall of the Council, men of all races and nations take their places in perfect equality – in the College of Cardinals, in the ranks of Archbishops and Bishops and heads of religious orders. All speak with equal freedom; all vote with equal force. To help us allay some of the prejudices which beset this country, it may be well to recall that some of the most effective voices within the Council have been those of African Archbishops and Bishops who by birth stand much closer to the hills and plains and wilds of Africa than the Negroes in our midst.

THE CHARITY OF POPE JOHN has not only transfused the Council, giving to it its unique pastoral spirit; it has also overcome many of the prejudices and antipathies of countless non-Catholic brethren, giving to them a new vision of the Church. It has awakened in all of us new Iongings and new hopes for Christian unity. Such charity within ourselves could enable us to purge from ourselves whatever racial prejudices and antagonisms we may still retain; it could help us to give to our non-Catholic Negro brethren such a vision of Christ’s Church as might open for them the door to spiritual truth.

Finally, the courage with which Pope John, in the face of so many difficulties and adverse predictions, called into being this Council, which may well prove to be one of the great turning points of the Church’s history, should lead us to face our own problems full of Christian faith and confidence and fortitude. In that ecumenical spirit of Christian renewal which in the words of Pope John, is meant to restore to the Church the simple, pure lines of her pristine beauty, let us – priests and people of this Archdiocese – face boldly and confidently the task that is before us, certain that with God’s help we shall achieve in the Church of this Archdiocese a holy unity, free from all stain of prejudice and from every defect of division or discrimination.

Sincerely yours in Christ,

+LAWRENCE J. SHEHAN

Archbishop of Baltimore

Also see: A 50-year legacy of racial justice