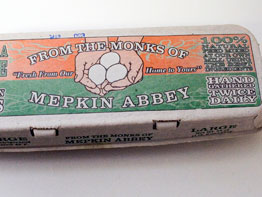

MONCKS CORNER, S.C. – The Trappist monks at Our Lady of Mepkin Abbey in Moncks Corner are looking at a variety of new ways to support themselves as they phase out their popular egg production business.

A 10-member advisory panel made up of Charleston-area business and banking executives, an organic farmer and two representatives of the Catholic community recently held an all-day brainstorming session on how the monks could continue to make a living.

Suggestions range from growing agricultural products as diverse as bamboo, mushrooms, heirloom corn and wheat, organic vegetables, and beets to be used as an organic road de-icer to pursuing such nonagricultural ideas as licensing beer; book scanning, the process of converting physical books into electronic books; and establishing a public cemetery on the Mepkin property.

The abbey announced in December that it would begin phasing out its 56-year-old egg business, citing pressure from People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals over the treatment of chickens as one of the reasons. Public protests and a threatened boycott by PETA that started in the summer of 2007 put unwanted pressure on the Trappist monks and interfered with their quiet life of prayer and work.

The end of the egg business meant the abbey had to find a new way to support itself. Sales averaging 9 million eggs a year have generated around $140,000, which is about 60 percent of the abbey’s annual income, according to Abbot Stan Gumula.

In a statement, Abbot Gumula said he was impressed with suggestions the panel generated.

“We hope to find a business that will respect the monastic tradition of working on the land and caring for the environment, and the advisory panel’s ideas certainly meet these criteria,” he said. “Our land is a wonderful resource, and … the panel has come up with great ways for us to use it creatively and wisely.”

Members of the panel agreed there should be an effort to find new products that can be sold locally so the monastery can maintain its strong connection with neighbors.

Mepkin’s eggs have been available in Piggly Wiggly grocery stores for years. Since the abbey’s establishment in 1949, the monks also have sold bread, flowers, timber, milk and beef cattle to support their way of life.

“There’s a lot of work and planning that needs to be done,” said panel member Dennis Atwood, retired chief financial officer for the Diocese of Charleston. “The abbey has a lot of challenges, including an aging workforce and not a lot of working capital to fund a new operation. The abbey is a wonderful resource and it’s a shame they’re having to face this.”

Atwood said he thought the public cemetery idea was a good one.

“There’s obviously got to be a future demand for that kind of service and a lot of people are going to want traditional burials,” he said.

Monsignor James A. Carter, pastor of Christ Our King Church in Mount Pleasant, said any agricultural venture would need to take into account Mepkin’s aging monks and existing resources. He said the monks will probably have to consider both long-range projects and a number of smaller projects that will help sustain the monastery in the interim.

“I suggested bamboo, especially because they have the property to plant bamboo and it doesn’t require a lot of care,” Monsignor Carter said. “The wood is becoming extremely popular for use in paneling and flooring, and in China they’ve even started using it for fabric. Some people say its softness is similar to cashmere.”

Monsignor Carter also suggested raising mushrooms or beets. In recent years, some communities in the northern United States have started using road de-icers derived from desugared beets.

“This beet substance is environmentally friendly and doesn’t corrode like salt,” he said.

The abbey also needs to consider how to maximize revenue that can be drawn from existing assets, according to Robert Macdonald, a retired museum director from New York who has been a close friend and consultant for the abbey for many years.

Macdonald said the panel suggested the abbey increase the use of its conference center by businesses and other groups and look into increasing its retreat program. Other suggestions included expanding the sale of existing abbey products such as fruitcakes and Drizzle, a syrup that can be used over desserts, meats and other dishes.

“The reality is that the abbey will probably be unable to make up the shortfall from the loss of the egg business solely through labor-intensive agricultural ventures,” he said.

“The solutions to this situation will be varied. It’s going to be a combination of saving money, finding new sources of revenue and increasing the income stream from current resources the abbey already has,” he said.