NEW ORLEANS – On April 4, 1968, a rifle shot at a Memphis hotel silenced the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and ripped apart a nation divided by race and war.

The same day Norman C. Francis accepted an offer by the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament to become the first lay president of Xavier University of Louisiana, the first historically black Catholic university in the Western Hemisphere.

Mr. Francis was just 37, and the university’s executive vice president already had spurned two previous offers from the sisters because he harbored dreams of becoming a “big-time lawyer like Perry Mason” to support his wife, Blanche, and their growing family.

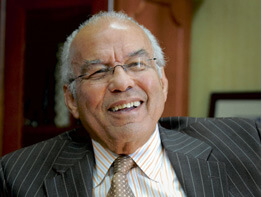

Forty years later, the 77-year-old Mr. Francis is the longest-tenured U.S. college president, a tribute to his rare mix of faith, flexibility and fortitude.

In 2005 when Hurricane Katrina turned Xavier into the lost city of Atlantis, Mr. Francis and his staff revived classes at the shipwrecked campus less than five months later.

He also agreed to serve as chairman of the Louisiana Recovery Authority, the quasi-governmental agency established by then-Gov. Kathleen Blanco that decided how to dole out more than $10 billion in federal recovery funds to civil parishes devastated by Katrina and Hurricane Rita.

From his second floor office in the Indiana limestone administration building constructed by St. Katharine Drexel – foundress of the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament and the one he’s “reported to” for the last 40 years – Mr. Francis juggles meetings, phone calls, e-mails, donors and new buildings.

Under construction is the $29 million, five-story Qatar Pharmacy Pavilion – a 55,000-square-foot structure funded largely by a $17.5 million Katrina grant from the government of the Middle Eastern nation of Qatar – which will keep Xavier at the forefront among American colleges of pharmacy.

Rising next from the mushrooming skyline will be the St. Katharine Drexel Chapel, designed by renowned Argentine architect Cesar Pelli.

All of this is happening at a university that places more African-American students in medical school than any other in the U.S., a school that came back from the dead even though 85 percent of its faculty, staff and administration, including Mr. Francis, lost homes because of Katrina. During his tenure Xavier’s endowment has grown from $2 million in 1981 to $80 million.

“I can tell you how God is good – all the time,” said Mr. Francis.

“We were all over the place, but there was a passion and a trust about coming back,” he said in an interview with the Clarion Herald, newspaper of the New Orleans Archdiocese.

“Honest to God, I never thought about the money or what it was going to cost. All I knew was we couldn’t stay out a year. If you did that, you would lose faculty and students,” he said.

Mr. Francis was dean of men at Xavier in 1961 when the Freedom Riders, a racially mixed group of students and ministers, attempted to ride a bus from Washington to New Orleans to test a Supreme Court decision allowing integrated interstate travel into the South.

The bus was ambushed in Alabama, but the small group of Freedom Riders eventually made it to New Orleans.

“They vowed they were going to come to New Orleans if they had to crawl,” said Mr. Francis, who agreed to let them stay on the vacant third floor of Xavier’s St. Michael’s Hall. “When they got out of the car they were bloody and beaten.”

Handling the social unrest that spilled over onto most U.S. campuses in the late 1960s was Mr. Francis’ biggest challenge. His legal training and common sense paid dividends.

Students staged a sit-on the steps blocking all access to classrooms, disregarding an agreement Mr. Francis had worked out that permitted them to sit on the first two steps but to move aside if students wanted to pass through.

“When that happened I called a meeting and brought everybody into the gymnasium,” Mr. Francis said.

He told them: “We’re not going to walk out of this gymnasium until you understand there will be no anarchy. If that has to happen, I know what I have to do, plain and simple.”

Two nights later, Mr. Francis agreed to meet with students, who presented him with a list of “non-negotiable demands.”

He put the paper down and began walking out the door, telling them: “Look, I know y’all didn’t go to law school, but unfortunately I still remember what a non-negotiable demand means. It’s non-negotiable, so there’s no sense in my wasting your time or my time.’”

Somebody in the group said, “OK, they’re negotiable,” and they reached an agreement on 10 of the 14 demands.

“After that first year, it was all downhill. It was no problem,” he said.

Mr. Francis said he is in excellent health, and the university is in the midst of a reaccreditation process scheduled to culminate in 2009.

“It’s very important for me to make sure it gets done and gets done well, and all of that is part of the succession plan,” he explained.

“When we get through doing what we have to do, anybody can walk in here because the community will have established where we want to go and how we want to do it,” he said.

The university plans to conduct a national search for his successor.

The key to his success, Mr. Francis said, has been hiring people he could trust and “people who are passionate about their work.”

“I always tell young university presidents to hire people who are smarter than you and then get out of their way,” Mr. Francis said.