VATICAN CITY – This year’s meditation for Pope Benedict XVI’s Good Friday Way of the Cross has a distinctly Asian perspective, referring to Hindu scriptures, an Indian poet and Mahatma Gandhi.

But the linchpin of this Eastern reflection is the passion of Jesus Christ. In that sense, it reflects Pope Benedict’s view of Christianity’s relationship with the non-Christian world – that the Gospel enlightens and fulfills the beliefs of other faiths.

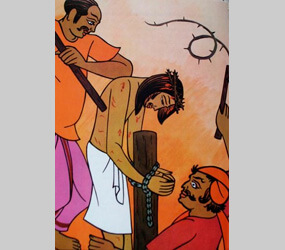

Indian Archbishop Thomas Menamparampil of Guwahati wrote the meditation on the 14 stations, to be read as the pope leads the candelit “Via Crucis” at Rome’s Colosseum.

The pope chose Archbishop Menamparampil, a 72-year-old Salesian, after hearing him deliver an impressive talk at last year’s Synod of Bishops on Scripture. The archbishop took it as a sign of the pope’s interest in Asia.

“His Holiness regards very highly the identity of Asia, the cradle of civilization. Moreover, our Holy Father has a prophetic vision for Asia, a continent very much cherished by him and his pontificate,” he said.

The immediate assumption among many Vatican observers was that the choice of an Indian would serve to highlight religious freedom issues in the wake of anti-Christian violence in parts of India.

Archbishop Menamparampil has assumed a leading role in conflict resolution among warring ethnic groups in northeast India, and his Good Friday meditation reflects his conviction that violence is never the way to resolve problems.

But he doesn’t explicitly mention anti-Christian discrimination. His aim here is not to list Christianity’s grievances, but to present its hopes and its answers to universal questions.

The archbishop is chairman of the Federation of Asian Bishops’ Conferences’ Commission for Evangelization, and has spoken many times about the receptivity of Asians to the Gospel. He has argued that the church’s presentation of the Christian message tends to be intellectual and doctrinal, but that it works best in Asia when it is more personal, experiential and poetic.

He follows that approach in his “Via Crucis” meditation, focusing on the way Jesus deals with violence and adversity, and finding parallels in Asian culture.

Condemned to death before the Sanhedrin, for example, Jesus’ reaction to this injustice is not to “rouse the collective anger of people against the opponent, so that they are led into forms of greater injustice,” the archbishop wrote.

Instead, he said, Jesus consistently confronts violence with serenity and strength, and seeks to prompt a change of heart through nonviolent persuasion – a teaching Gandhi brought into public life in India with “amazing success.”

He cited another Christian success story in India, Blessed Mother Teresa of Calcutta, when reflecting on how Simon of Cyrene helped Jesus carry his cross.

Simon was like millions of Christians from humble backgrounds with a deep attachment to Christ – “no glamour, no sophistication, but profound faith,” in whom we discover “the sacredness of the ordinary and the greatness of what looks small,” the archbishop said.

It was Jesus’ plan to lift up the lowly and sustain society’s poor and rejected, and Blessed Mother Teresa made that her vocation, he said.

“Give me eyes that notice the needs of the poor and a heart that reaches out in love. Give me the strength to make my love fruitful in service,” he said, borrowing a line from the Indian poet Rabindranath Tagore.

Archbishop Menamparampil echoed one of Pope Benedict’s favorite themes when he spoke about Jesus being mocked before his crucifixion. Today, he said, Jesus is humiliated in new ways: when the faith is trivialized, when the sense of the sacred erodes and when religious sentiment is considered one of the “unwelcome leftovers of antiquity.”

The archbishop said the challenge today is to remain attentive to God’s “quiet presences” found in tabernacles and shrines, the laughter of children, the tiniest living cell and the distant galaxies. His text reflected the idea that Jesus’ own life embodies Indian values, including an awareness of the sacred through contemplation.

“May we never question or mock serious things in life like a cynic. Allow us not to drift into the desert of godlessness. Enable us to perceive you in the gentle breeze, see you in street corners, love you in the unborn child,” he wrote.

Archbishop Menamparampil seemed equally comfortable drawing from the Western and Eastern Christian traditions. He illustrated the “mystic journey” of personal faith set in motion by Christ’s death on the cross with a verse from a psalm and an eighth-century Irish hymn.

He ended with a meditation on Jesus’ entombment, borrowing insights from the Eastern spiritual distinction between reality and illusion.

“Tragedies make us ponder. A tsunami tells us that life is serious. Hiroshima and Nagasaki remain pilgrim places. When death strikes near, another world draws close. We then shed our illusions and have a grasp of the deeper reality,” he said.

He quoted a prayer from the Hindu holy writings, the Upanishads: “Lead me from the unreal to the real, from darkness to light, from death to immortality.” He said this was the path taken by the early Christians, who were inspired by Jesus’ life to carry his message to the ends of the earth.

That message remains a simple one today, he said: “It says that the reality is Christ and that our ultimate destiny is to be with him.”