WASHINGTON – When most provisions of the new health reform legislation take effect in 2014, an estimated 32 million people who had been without health insurance when the reform effort began will be insured. But who will be caring for them?

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services predicts a shortage of 21,000 primary care clinicians in 2015, while the Association of American Medical Colleges projects that as many as 150,000 physicians across all specialties could be needed to meet demand by 2025.

The year 2014 is also when the incoming freshman class at Georgetown University School of Medicine will graduate and begin their residencies, confronting the challenges of a health care system that bears little resemblance to the one they grew up with.

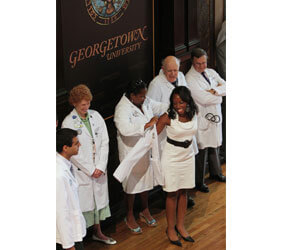

“A lot of people have been telling me that it’s a bad time to go into medicine, but everybody’s going to need a doctor throughout their lifetimes,” said Michael Narvaez, who received his first white coat, marking the start of his career as a physician, along with nearly 200 fellow students at the school’s white coat ceremony Aug. 6.

Narvaez, who played football at the University of Notre Dame, hopes to practice orthopedics and sports medicine, a choice that was inspired when he tore a major ligament in his knee during his sophomore year of high school.

“Having the experience from the patient’s perspective and … seeing how the doctor helps his patients, I was inspired to want to give that kind of care,” he said.

Maggie Burke, a Brown University graduate, said she hopes to become a primary care physician. “Patients are really why I got into this, and forming those relationships is really important to me,” she said.

Burke and several other students interviewed by Catholic News Service after the white coat ceremony said they chose Georgetown medical school because of its emphasis on the Jesuit concept of “cura personalis” – care for the whole person, body, mind and soul.

“When you take that whole-body approach, you are going to find some other issues underlying (the patient’s) physical disorder,” said Nikola Lekic, a Boston College graduate who also earned a master’s degree at Georgetown before starting medical school. As a doctor, he wants to be “interacting with the patient and not just giving orders to the patient.”

But Lekic, who minored in French at Boston College, plans to use his medical training next summer – and perhaps beyond – to assist those affected by the Jan. 12 earthquake in Haiti.

“There are still a lot of troubles down there,” he said. “I think that much of the Third World, especially Haiti at this moment, needs our help.”

Although Burke was the only one of the five Georgetown students interviewed by CNS who felt sure she would go into primary care, also known as family medicine, there are signs of a renewed interest in family medicine and some extra incentives from the government in the health reform bill.

The National Resident Matching Program, which assigned more than 16,000 medical school seniors to their next three to five years of residency training earlier this year, saw a 9 percent increase in family medicine residents over 2009.

The assignments are made by matching the students’ preferences with the hospital residency programs that select them.

Two other primary care specialties also saw increases in positions filled by U.S. medical school seniors – internal medicine (up 3 percent) and pediatrics (up 2 percent).

The Prevention and Public Health Fund created as part of the health reform legislation will provide $168 million to train 500 new primary care physicians over the next five years, $30 million to train 600 additional nurse practitioners and $32 million to create 600 new physician assistants, who practice medicine on a team with a supervising physician.

Other provisions of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act offer incentives for primary care clinicians to practice in rural or other underserved communities through scholarships, educational loan repayments or tax incentives; provide bonus payments for physicians who practice primary care for Medicare patients; and support job training in the health care field for low-income and low-skill workers.

“Combined with the earlier investments made by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, the provisions of the Affordable Care Act will support the training, development and placement of more than 16,000 new primary care providers over the next five years,” according to a fact sheet distributed by HHS.

Interest in obtaining a medical school education is high. Georgetown’s class of 2014 – made up of 91 women and 105 men – was culled from more than 11,500 applicants.

At the Aug. 6 ceremony, each student received his or her white coat from a mentor who helped shape the student’s career choice. Each also was given a pin representing Georgetown’s motto of “cura personalis.”

Dr. Donald M. Knowlan, professor emeritus of medicine at Georgetown, told them not to be discouraged by the challenges ahead.

“Despite everything you hear about health care reform and other obstacles, this is still the greatest career at the greatest time,” he said. “No one has had a greater opportunity or a better chance at medicine than the class of 2014.”