LUBECK, Germany – As the Nazi executioner beheaded three Catholic priests and a Lutheran pastor, one after another in a matter of minutes, their blood flowed together, creating a powerful symbol for ecumenism in northern Germany.

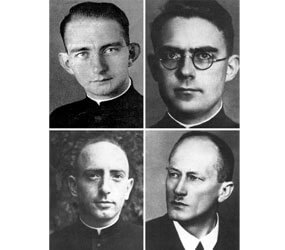

On June 25, the three Catholic martyrs of Lubeck – Fathers Johannes Prassek, Eduard Muller and Hermann Lange – will be beatified in the historic city’s Sacred Heart Church, a stone’s throw away from the Lubeck Cathedral, the ministerial home of the Rev. Karl Friedrich Stellbrink, their Lutheran counterpart. Rev. Stellbrink will be honored in a special way that day as well.

The four were executed in Hamburg Nov. 10, 1943. All had been found guilty of disseminating anti-Nazi material – such as the homilies of Cardinal Clemens von Galen of Munster – and other “treasonous” activities.

Although they were just four of more than 1,600 victims of Nazi political executions that year, their case drew the particular attention of Adolf Hitler and propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels. Hitler reportedly intervened personally in the case of the four clerics, formulating the charges and instructing prosecutors on their strategy.

After the four were sentenced to death June 23, 1943, in a trial widely considered a farce, Goebbels wrote in his diary: “I urge that the death sentences will in fact be carried out.” An appeal for clemency by Catholic Bishop Hermann Berning of Osnabruck was rejected.

Father Franz Mecklenfeld of Sacred Heart Church told Catholic News Service that news of the beatification was received with “immense joy” by his parishioners.

It also is being followed “with great interest in the city of Lubeck,” traditionally a Lutheran stronghold. In September, the daily Lubecker Nachrichten published a series of articles on the lives of the four martyrs.

“The martyrs have a great significance for the city,” Father Mecklenfeld said. “They have become ‘shining towers’ in the city of Lubeck,” where the skyline is famous for its seven Gothic church spires.

The notion of beatifying the three Catholics when their Lutheran companion cannot be honored in the same way has given rise to some controversy. The Rev. Heinz Russmann, a Lutheran pastor in Lubeck, wrote that the beatification would represent a painful division that would be harmful to ecumenism.

Either all four should be beatified, or none, he wrote.

His view is shared by the conservative local politician Hans-Lothar Fauth, a Catholic, who has said that all four have long been publicly acclaimed as saints, regardless of denomination, and therefore require no official recognition.

Father Mecklenfeld said his parish always has been sensitive about maintaining the ties among all four martyrs.

Ecumenical relations in Lubeck are marked by the shared martyrdom. Pope Benedict XVI, a German, has recognized the significance of that friendship.

In an address to the German ambassador to the Vatican Sept. 13, he said the friendship among the clerics while in jail “represents an impressive witness to ecumenical prayer and suffering which in many places flowered among Christians of different denominations during the dark days of national socialism. We may regard these witnesses as shining lights on our common ecumenical path.”

Father Lange’s writings bear out the pope’s sentiment. In a July 1943 letter, he wrote: “The suffering borne in common over the last years has brought the two Christian churches closer to one another. The shared imprisonment of the Catholic and the evangelical (Lutheran) clergy is a symbol of this community of suffering, but also of reconciliation.”

Rev. Stellbrink, 49 when he died, has been described as a prickly character who initially was an eager supporter of the Nazi party. The World War I veteran soon became disillusioned with Nazism, especially its anti-clericalism, and began to criticize it. He was expelled from the party in 1937 for refusing to denounce his friendship with Jews.

In 1941, he met Father Prassek at a funeral and increasingly began speaking against the Nazis by building a friendship with the younger priest, who had resolutely opposed Hitler’s regime.

Rev. Stellbrink was the first Protestant cleric to be executed in Germany. Unlike his Catholic friends, he received no support from his church, which rehabilitated him only 50 years later, noting its “pain and shame” at the disgraceful treatment of the heroic pastor.

Father Prassek, 32, regularly preached against Nazism and ministered illegally to forced laborers from Poland, even learning Polish for that purpose. Just before his arrest Father Prassek was honored for his courage in rescuing people during the carpet bomb attack on Lubeck – the first on any German city – on Palm Sunday 1942.

Like his companions, he expected to be executed after their arrest. On the day of the court’s judgment, he wrote: “God be praised, today I was sentenced to death.” Later, physically broken after more than a year of torture and hardship in jail, he looked forward to his execution.

“To be allowed to die fully conscious and quietly prepared is the most beautiful thing of all,” he wrote.

Father Muller, also 32 and a priest for just three years when he was executed, was a quiet man, popular among local youth. Though regarded as mostly apolitical – he never preached publicly against Nazism – he acknowledged Hitler’s ideology as irreconcilable with Christianity and refused to collaborate with the Hitler Youth, which had courted him.

Father Lange, 31, was parochial vicar at Sacred Heart Church and ministered to youth and men at the parish. A reform-minded Catholic, he was perhaps the most politically active of the four. He distributed pamphlets and privately accused Germany of war crimes. He even told a soldier that a true Christian could not fight on the German side in the war. Father Lange’s residence was raided by the Gestapo a year before his arrest.