WASHINGTON – With the bulk of U.S. population growth coming among Hispanics, the Catholic Church must get out ahead in welcoming Latino newcomers or they will become involved in other institutions and activities instead, cautioned panelists at a conference on immigration and the church.

Some types of welcoming might include offering Mass in Spanish, creating an environment around parish property where immigrants without family will feel at home hanging around with friends there, or being able to rally support at Catholic universities for the DREAM Act, said Father Virgilio Elizondo, professor of pastoral and Hispanic theology at the University of Notre Dame’s Institute for Latino Studies.

“Immigrants bring with them a profound faith that God is with them,” he said at a daylong conference on the pastoral, policy and social implications of immigrants in the Catholic Church. “Yet many are not made welcome in our churches.”

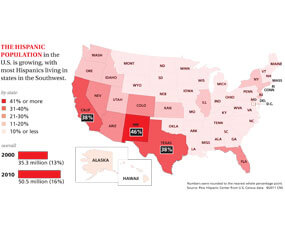

Father Elizondo was among panelists at the March 21 event co-sponsored by The Catholic University of America and the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops. Just a few days later, the Census Bureau released data from the 2010 census showing that one in six Americans is Hispanic, their largest percentage of the population to date, up by 43 percent in a decade.

And Latinos are a young demographic, making up 23 percent of the under-17 population, compared to 16 percent of the total U.S. population, according to the census. It showed that though most Latinos still live in just nine states as they have for generations – Arizona, California, Colorado, Florida, Illinois, New Mexico, New Jersey, New York and Texas – the Hispanic population more than doubled in nine others, primarily in the Southeastern region. Those include Alabama, Arkansas, Kentucky, Mississippi, North Carolina, Tennessee, South Carolina, Maryland and South Dakota.

The data affirmed what speakers at the conference said about the church needing to recognize that it has new members in places where Catholics have been a small part of the population.

Immigrants need help adjusting to their new home, learning English and figuring out paths to leadership in society and in the church, he said. From the parish office and pastoral staff through organizations like the Knights of Columbus, the various people and functions of the church need to consciously reach out to these newcomers, he added.

“Even if people walk out,” when a priest preaches about the need to welcome newcomers, as sometimes happens, said Father Elizondo, the church’s pastoral responsibility is to embrace those who may change the demographic face of a community.

“This is a moment of real challenge,” he said. In some places, that will mean confronting racist attitudes that people may not recognize in themselves, Father Elizondo said, adding that the current tone of political debate about immigration helps mask some people’s xenophobia in arguments such as “what part of illegal don’t you understand?”

In the same panel discussion, Timothy Meagher, associate history professor at Catholic University, explained that the only reason the Catholic Church in the United States is as large as it is today – about 25 percent of the population – is because of the massive immigration of poor, low-skilled people from Ireland, Italy and Germany in the 19th century.

Then, as now, many of those immigrants came because what is now called globalization undermined entire economies.

Poor farmers and artisans found themselves undermined by lower-cost agriculture and factories in other countries when railroads and steamships made it possible to send food and manufactured goods around the world, Meagher said. Much like today, those who were pushed out emigrated to the United States, where growth in low-skilled jobs offered them a chance to support their families.

Another panelist, Jesuit Father Alan Figueroa Deck, executive director of the USCCB’s Secretariat of Cultural Diversity in the Church, said there is “no doubt this is a critical moment in the history of the church.” The church’s young people are no longer predominantly of European ancestry, he noted, adding that the church’s leadership, institutions and even the style of worship “must take this transformation into account.”

It’s because of recent immigration that the Catholic Church has become much more established in all parts of the country, he said, giving the example of North Carolina, where the Catholic population has doubled “because of immigrants.”

Although there’s been great progress in the past 60 years in developing leadership capability among Hispanic Catholics and ministries for them, Father Deck said much of the church doesn’t recognize that “U.S. Catholicism will be different” because its growth is coming from Hispanics.

For instance, the people involved in the charismatic renewal and Cursillo movements are primarily Hispanics and more than half of Hispanic Catholics say they have been influenced by the charismatic renewal movement, he said.

“This is a way of being Catholic that’s more celebratory and festive,” said Father Deck. Holding onto these Catholics will take evangelization that appreciates such culture, he said, and avoids trying to make people with different traditions fit into the “American” type of church. That runs the risk of driving these new generations not toward evangelical churches, but toward a secular attitude that doesn’t include any faith.

“We’re Americanizing people out the front door of the church,” he said.