EMMITSBURG, Md. – In the final days of June 1863, the Civil War came perilously close to home for the Daughters of Charity in Emmitsburg.

Days before the Battle of Gettysburg, the acres of their farmland property at the foothills of the Catoctin Mountains were used as a camp for tens of thousands of Union soldiers while their generals stayed in the former home of the order’s founder, St. Elizabeth Ann Seton, and planned battle strategies.

The troops moved on to fight one of the bloodiest Civil War battles just 15 miles away from the sisters, and when the fighting ended, leaving tens of thousands dead and wounded, the Daughters of Charity were among the first civilians to arrive and care for Union and Confederate soldiers.

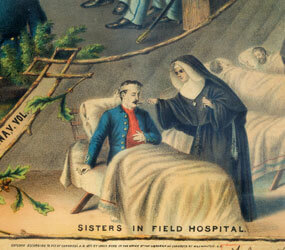

The sisters provided food, water, bandages and basic medical care. They also gave spiritual solace to soldiers who requested it: praying with them, distributing religious medals, baptizing the dying and writing letters home to soldiers’ families.

At Gettysburg and other Civil War battles, at least 300 Daughters of Charity ministered to soldiers on both sides of the war. In all, more than 600 sisters from 12 religious orders responded to this national crisis by doing everything from bandaging soldiers in the battlefield to coordinating makeshift hospitals.

St. Francis Xavier Church in Gettysburg served as one of these improvised hospitals. The church’s vestibule became an operating room, its sanctuary was a recovery room, and the pews functioned as cots for more than 200 wounded soldiers.

The church, which is still a parish today, pays tribute to the nuns’ ministry with a stained-glass window depicting the Daughters of Charity caring for wounded soldiers.

Those who visit not only the Gettysburg church but the Emmitsburg Shrine of St. Elizabeth Ann Seton are reminded right away that these spots had historical significance during the Civil War by signs marking Civil War trails and posted descriptions of events that took place 150 years ago.

But the general public might not be so aware that nuns were on the scene at that time providing a much-needed service.

Sister Betty Ann McNeil, a Daughter of Charity and the provincial’s archivist, said the sisters’ unique role has been “under-told” in Civil War documentaries and publications. She attributes this gap to a lack of public relations, saying the sisters didn’t take pictures of themselves on the battlefields or promote the work they were doing.

There is at least one public tribute to the work of these women: the Civil War Nurses Memorial in Washington near St. Matthew Cathedral. The monument, erected in 1924, is inscribed with the words: “They comforted the dying, nursed the wounded, carried hope to the imprisoned, gave in his name a drink of water to the thirsty.”

Sister Betty Ann told Catholic News Service Sept. 15 that little is known about the role of these sisters in history because they simply were responding to the needs of the time, not unlike the work these sisters continue today in caring for the sick and helping those in need.

She personally knows a lot about the work of the sisters because she has pored through reams of handwritten documents detailing their duties during the war. Based on these accounts she edited the trilogy “Charity Afire” recounting the sisters’ Civil War ministry in Pennsylvania, Maryland and Virginia. The books were published this year to mark the 150th anniversary of the start of the Civil War.

This year the shrine also opened a permanent exhibit in its visitor center showcasing the nuns’ role in the war and is in the process of restoring Our Lady of Victory statue erected by the Daughters of Charity immediately after the war. At the time, the sisters had promised that if their land was protected from war, they would put up a statue on the property in thanksgiving. The statue, worn from more than 100 years outdoors, will be part of the sisters’ Civil War exhibit once it is restored.

During her research, Sister Betty Ann was particularly inspired by Sister Juliana Chatard, a young Daughter of Charity who longed to be in the field of action. Eventually this young woman, who was from the North, was sent to Richmond, Va., and made an administrator of a soldiers’ hospital there. Sister Betty Ann quotes the sister’s experience at St. Ann’s Military Hospital in a 2007 article for the Vincentian Heritage Journal.

According to Sister Juliana’s account, it was difficult to describe the routine at the military hospital because “to lay the scene truly before you is beyond any human pen. All kinds of misery lay outstretched before us.”

Describing the 1862 Battle of Richmond, Sister Juliana said fighting during the weeklong battle started each day at 2 a.m. and ended around 10 p.m. with bombs “bursting and reddening the heavens” just yards from the hospital door. She also said the sisters at the hospital were shaken by cannon firings and the “heavy rolling of the ambulances filling the streets bringing in the wounded and dying men. The entire city trembled as if from an earthquake with the exception of few short hours.”

As Sister Betty Ann sees it, Sister Juliana’s ministry was similar to what so many of these sisters were doing during a time of great national turmoil.

“Her charity knew no bounds,” she said. “Her love embraced the Northern soldier who was dying as well as the Southern soldier who was thirsty.”