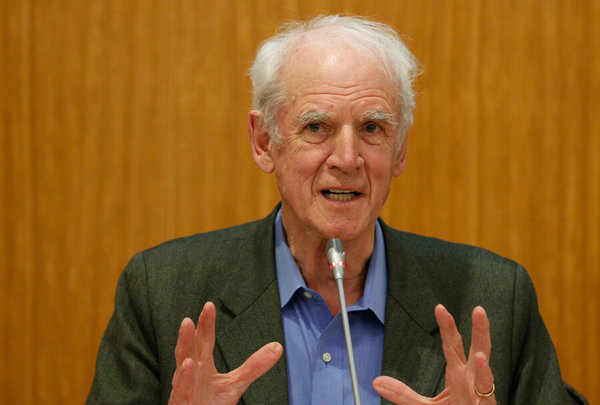

VATICAN CITY (CNS) — The heady realm of philosophy got special accolades in November when the preeminent Canadian philosopher, Charles Taylor, won the Ratzinger Prize.

The prestigious award, a sort of “Nobel Prize in Theology,” is given to scholars who stand out for their scientific research in the field of theology.

But the committee that chooses the winners also seeks to include experts who are not strictly theologians or specialists in sacred Scripture, but who still enrich theological studies through their work as artists, scientists or philosophers, said Cardinal Gianfranco Ravasi, president of the Pontifical Council for Culture and a committee member.

That is why “the impressive individual, Charles Taylor,” was one of the winners for 2019 — because he has offered an in-depth look at secularization — a phenomenon of huge importance for Pope Benedict XVI, the cardinal said in an interview with Vatican News.

Pope Francis praised his predecessor, the “theologian and pastor who … gave us the example of seeking the truth in which reason and faith, intelligence and spirituality, are constantly integrated.”

To keep the Christian faith “vital and to make evangelization effective,” theology has an obligation to be in active dialogue with all cultures, which change over time and across the globe, Pope Francis said in a speech presenting the Ratzinger Prize to the winners at the Vatican in early November.

In his extensive career over the decades, Taylor, an 88-year-old professor emeritus of McGill University in Montreal, has offered an important analysis of how Western culture changed and secularization developed.

“We are indebted to him for the profound manner in which he has treated the problem,” Pope Francis said, because Taylor’s work “allows us to deal with Western secularization in a way that is neither superficial nor given to fatalistic discouragement.”

St. John Paul II also appreciated Taylor’s insight, welcoming him among the many leading intellectuals invited to the papal summer villa in Castel Gandolfo over a series of summer seminars for Catholics and non-Catholics to exchange ideas and discuss pressing problems of the modern world.

“Throughout his career, Charles Taylor has staked an often lonely position that insists on the inclusion of spiritual dimensions in discussions of public policy, history, linguistics, literature and every other facet of humanities and the social sciences,” said the late John M. Templeton Jr., president of the John Templeton Foundation, when it awarded Taylor its prestigious prize in 2007.

A once-lapsed Catholic who “thought” his way back to the faith, Taylor has criticized the exclusion of religion from the public sphere and sees any disregard for the spiritual or transcendent as being harmful to society.

But he also has criticized the false notion that religion had simply died in the modern era; what has radically changed, he told the Vatican newspaper in mid-November, are the cultural conditions people live in, which affect how they seek and live out their spiritual lives and relate to religion.

In fact, if secularization is seen as a situation in which religious belief is no longer automatically accepted or imposed, a positive consequence is that people are usually seeking a deeper, more meaningful relationship with faith, he told the paper.

Taylor refers to faith as “the idea of journey” — the same dynamic Pope Francis talks about when he talks about what living a Christian life is like.

Rather than faith as a fixed form of belonging or identity, one can think of people being on a journey, Taylor said, each one driven by different interests, desires and paths, but all heading toward the same divine horizon, living “the entire Christian tradition in a contemporary way.”

“In this era, there is an enormous amount of spiritual seeking, and this seeking focuses on sources of very different eras, different traditions,” because different people are attracted by different things, he said.

The antimodernist fears of Pope Pius X “didn’t make sense,” he said, because, far from destroying tradition, theologians were rediscovering and reexamining large parts of Christian tradition and were offering greater freedom in people’s relationship with tradition.

One of the reasons he admires Pope Francis so much, Taylor said, is “because he understands that what is important today isn’t the defense of tradition, but is communication, letting a breath of fresh air into the church.”

People today are searching, looking for who they are, which “is something that is very close to Christian tradition and the question, what is my vocation? What gives meaning to my life?” he said.

If religion instead becomes “a political identity, when it is twisted for political ends, terrible things happen. This is happening in the Muslim world and in some parts of the Buddhist world,” he added.

When asked about the role of Christians in politics, Taylor said: “I think Christians must be involved in politics. This is inevitable” because it is rooted in a sense of personal and communal responsibility — to make the world a better place.

“As a Christian, I always feel tied to certain values and positions and I want to defend them, even in the political arena. But it is important to understand in which situations it is good to act and which ones to avoid,” he said.

Dialogue is the principal path to take in the political world, being open and having “a certain amount of humility and thinking that perhaps we, too, may be wrong. But in the end, as citizens, we have to act with what we have, with our beliefs and interpretations.”

Copyright ©2019 Catholic News Service/U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops.