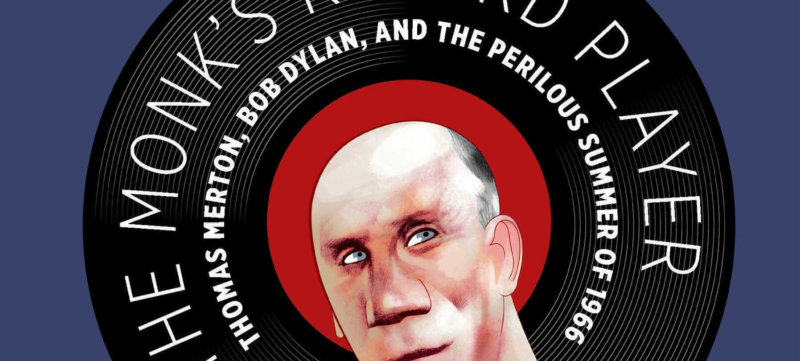

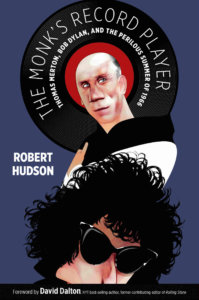

“The Monk’s Record Player: Thomas Merton, Bob Dylan and the Perilous Summer of 1966” by Robert Hudson. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing (Grand Rapids, Michigan, 2018). 247 pp., $23.

Robert Hudson is a writer and editor, a recognized Bob Dylan scholar and a member of the International Thomas Merton Society, and here is his starting point: “Although (Father Thomas Merton and Bob Dylan) lived their lives a thousand miles apart, their souls were next-door neighbors.”

Hudson describes his book as “an intentionally selective biography” and “a parallel biography” which “juxtaposes events in Father Merton’s life with those in Dylan’s”; it is a book that “shows Dylan’s personal and artistic influences on the monk.”

Hudson declares that it is nearly impossible to overemphasize Dylan’s personal and artistic influences on Father Merton, a Trappist priest. For, Hudson writes, “Merton recognized a prophetic voice when he heard one.” In particular, Hudson continues, Dylan’s music had a therapeutic effect on Father Merton at a time when the priest’s life was in personal crisis.

“The Monk’s Record Player” is divided into three parts. The first two focus on Father Merton (April 1941 to August 1965 and March to July 1966) with a “Dylan Interlude” — a brief look at aspects of Dylan’s life and music — following each. The third part looks at Dylan and the impact of his music on Merton.

One of the most attractive characteristics of Hudson’s book is his lively writing style, so much so that it rivals a fictional treatment of the topic. This isn’t fiction, of course, for the solid research and many enlightening insights could only belong to a semi-biography such as this one.

Hudson’s understanding of Father Merton and his life stands up well, and his approach is unique compared to other similar books.

Two puzzlements, however: First, Father Merton always referred to his deceased younger brother as “John Paul.” Thus, Merton aficionados will be perplexed when Hudson, for reasons obscure, refers to the priest’s brother as “Paul.” Second, Hudson’s understanding of the monastic vows seems lacking, as he declares, for example, that a postulant takes vows and a novice takes solemn vows, both of which are simply untrue.

The grasp of Dylan, his life and his music that Hudson exhibits is solidly informed, and most readers will find it enlightening. Some may be mystified by comparisons and parallels Hudson outlines between Dylan and Father Merton, but even when this happens it is likely that the reader will find Hudson’s perspective intriguing.

The great thing about this book is that it runs circles around any mere biographical treatment of either Father Merton or Dylan. It makes connections between themes in both men’s lives unlikely to be found anyplace else.

One example: “Merton realized,” Hudson writes, “that silence and music are entwined, fellow travelers.” Silence and music? Here and in numerous other observations, this book teaches lessons in spirituality the reader may not expect but from which he or she will benefit deeply.

Copyright ©2018 Catholic News Service/U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops.